StateHooded, part I: Haoles of Humacao

Two native Hawaiians defended their village against an armed foreigner, and now they are doing years in federal prison. Here is lo que le pasó a Hawai’i.

“For the colonized, to be a moralist quite plainly means silencing the arrogance of the colonist, breaking his spiral of violence, in a word ejecting him outright from the picture.” - Frantz Fanon

The village

Kahakuloa is the last standing native village on Maui, kept protected for millennia.1 Tucked into the northern coastal valleys and accessible only by roads that frighten foreigners, Kahakuloa avoids the millions of tourists that come to Maui every year, keeping their forests rich, their bays healthy, and their village quiet. It’s not a large village, home to some 25 families that all make up one big collective family.2 It’s the type of place that Nat Geo Traveler features, calling it “a step back in time to old Hawai’i”, and warning that “Kahakuloa is not a place where one sees tourists, or non-Hawaiians for that matter.”3

Preston Grove grew up there. His name comes from his father, who is white, but as a baby he was sent to live with his mother’s parents up in Kahakuloa to learn “how to do everything a Hawaiian should do.” He’s 43 now and lives in Southern California, but we spent hours talking about life growing up in the village, “In Kahakuloa we live the old Hawaiian ways. We may not live in grass shacks or anything like that but we live the old Hawaiian ways. We take care of the land, we live off the land, we take care of the ocean.” Even as Maui imports most of it’s food, Kahakuloa villagers still tend their taro patches. While most of Maui’s fisheries have become barren, Kahakuloa’s bay is a nursery for sharks and whales. “I’ve seen a humpback whale give birth once. It was fucking awesome and scary at the same time.”

Growing up, Preston used to see entire schools of fish swimming through the bay. “You could see them like a cloud moving through the sky. And the whole village, when the school used to come into the bay, would get ready. It was something to see.”

The entire village came down and shared in the work. A few people were out in the water maneuvering boats and nets while someone up on the mountain held flags and watched over the fish. As the school traversed the water, the flags signaled for the boats to move in response, “it was all coordinated like a dance.” Once surrounded, the fish were brought from the bay into the river. The crowd would take all the fish out of the nets, hundreds, and put them in big plastic barrels that Preston’s grandfather kept “and everybody got fish, everybody.” Anything left over went to families outside the village, and what remained after that would go to a store to recoup for gas and repairs for the boats, “but everybody got their fair share. You put in the work, you get your share. It was something to see.” But they never took more than what was needed, “that was bad luck.”

“Our village is very sacred,” Preston tells me. “There is a heiau (ancient religious site) in this little patch of jungle that was right across the river. It was small but we would play Army.” His mom would watch from the house, “she would look down to the exact places we were playing and she used to see a fire and shadows of people dancing hula down there.” Ancestors visited the village often. A villager would be walking in the woods, going to get water, and hear footsteps behind them. They stop but the footsteps keep going right past them. It happened to Preston once.

“And every huaka’i po night the night marchers would come. When the sky is black—no moon, no stars, no nothing. Nobody would leave their homes that night, that was their night not ours.” A house that is improperly constructed, impeding the paths of the night marchers, can end up ruining the lives of its occupants. Preston’s seen it happen.

Preston’s grandparent’s house, where he grew up, is right next to the bay. “I would sit in my living room watching tv and I hear “pshh pshh” and I’d be like what the fuck was that?” He’d spring off the couch running barefoot out of the house to swim with a pod of porpoises as it passes through the bay. “I’m grabbing my goggles, running into the water. You know, you hear the echo sonar and you can feel that shit bouncing off of you.”

Life moves slowly in the village. The one-room Kahakuloa Church was built 135 years ago, when Maui was still part of the Hawaiian Kingdom. To this day much of the property in the village has never been bought nor sold. The people know they have something special, and they will do what is necessary to protect it.

The fight

It’s 2014, the eve of Valentine’s Day. To Preston’s regret, he is not around. He joined the Army a few years back and has a few months left in Afghanistan. The Kenyan-American born just two islands over is still occupying the White House. Michael Brown is still alive. Preston’s grandfather is in the front yard doing some yard work.

Preston’s grandfather grew up in Kahakuloa, like his father’s father. Preston told me he did a lot for Kahakuloa, “He arranged and got grants to repair the ditches. He made sure everything stayed right and everything stayed running smooth.” Grandpa was tough—the whole village is a certain kind of tough, by necessity—but serving in Korea made Grandpa someone you did not want to cross. He was known to have a short fuse but “he was fair, a just person.” Preston looked up to him. “If my life could equal just one portion of what that man is—that man was—I would’ve done something.“

Grandpa never hesitates to defend his village. There’s an old grainy video of him on YouTube doing exactly that. It’s not clear why the white couple who posted it are trespassing on his property, but he clearly struck some fear in them with his booming ‘get the hell out of here!’ Grandpa never went looking for trouble, he would never throw the first punch, “but if you throw that punch you’re gonna regret it.”

Grandpa raises his gaze to meet a shiny black Land Rover at the village entrance. He can’t believe what he’s seeing, Chris Kunzelman has returned. Last week Chris rammed his luxury truck into Grandpa’s gate before letting himself and his friends into the old vacant house which Grandpa had originally built for one of Preston’s uncles. The village was shocked. Someone locked the gate after he rammed it so Chris cut the chains when he left.

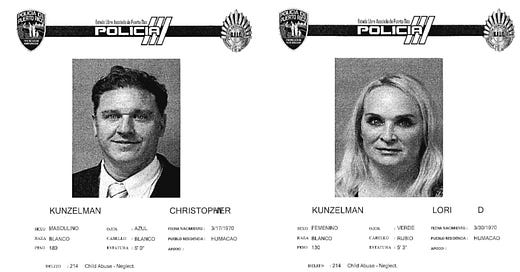

Chris Kunzelman, 40, is a multimillionaire who flew in from Scottsdale. Chris spends a lot of his time overseas. He and his high school buddy, a fellow millionaire, have spent the last fifteen years traveling together throughout Africa, Asia, and Latin America, making what is to become a feature film about “the human experience.” It’s a documentary of the duo's misadventures amongst indigenous tribes and poor peoples across the world, and is soon to be released by MGM, though Chris believes it deserves a never-ending Netflix series. On these trips, Chris likes to keep a brick of 500 one dollar bills in his bag in case things go wrong, which they often do, because “it looks amazing.” In Chris’ world, “money can fix most things.”4

Chris grew up on 200 acres outside of St. Louis yet still believed himself poor. For the last two decades he’s been flipping houses, making more money than he knew what to do with. In his twenties he took over the family jewelry business. In his thirties he got out of St. Louis by buying up four parcels of Arizona desert and turning them into a massive ranch equipped with an in ground pool. When the city fined him for excessive environmental destruction, Chris sued.5 He is used to things going his way.

Chris is a different kind of tough than Grandpa and the people of Kahakuloa. He was once the bodyguard for Menlo Smith, business tycoon from the family of Mormon prophets. Menlo founded the company that made Fun Dip, Pixie Sticks, Spree, and SweeTarts, amassing a small fortune. One of his favorite hobbies was to helicopter into isolated mountain ranges to ski the untouched slopes. He hired Chris to keep him safe, the adventurer who feared neither crisis nor native.

Chris pulls up to the gates, again locked, demanding to be let back in. When the villagers say no, Chris cuts the chains a second time. His vehicle, this time followed by another car, continues again to the old vacant house and parks underneath. Four people get out and quickly unload some boxes and tools. The second car leaves, but Chris and a relative stay behind.6

The village has had enough. People are outside shouting for the intruders to leave. Grandpa takes the lead, walking down to the house to confront the two men. We don’t know exactly what Grandpa said or how Chris reacted—the court documents make no mention of it—but according to Preston, while Grandpa is demanding the men leave, Chris pulls out a gun. “My grandfather ain’t afraid of that,” Preston warns.

Grandpa’s smart, he doesn’t take the bait. Preston’s younger cousin Kaulana Alo-Kaonohi, however, is not going to just sit back and watch this guy continue to threaten his family. He and his friend Levi Aki, both big young men in their early 20s, walk over to tell the strangers to leave. When they reach Chris he is already pointing a phone at them, recording, and repeating that he owns the place. Behind the phone, they see a $6,000 gold chain and a pistol; Chris’ entitlement is radiating.

It’s not long before Kaulana and Levi boil over, punching and kicking Chris who continues to refuse to leave. “You’re moving too fucking slow for me, bruh,” Kaulana pleads, trying to end the conflict as quickly as possible. In the chaos Kaulana picks up a shovel and hits Chris with it, still repeating that he needs to go. At some point the pistol goes flying, the young men take the extra clip out of Chris’s pocket, grab his phone out of his hand and the gold chain off his neck and toss it all into the ocean. Finally they are able to force the strangers back into their luxury truck and out of the neighborhood.

Chris leaves with a gash on his head and fractured ribs, yet before seeking medical attention, he first goes to the Maui police, who show little interest in his sob story. He’d already come in last week after the first gate incident demanding a police escort, which they advised against, knowing it would be a bad introduction coming in so hot. So when Chris says that it wasn’t his behavior that led to the fight, but rather that “they don’t like my skin; I have the wrong color skin,” Maui PD rolls their eyes. “The police officer refused to write down anything about race, nothing,” Chris later complained in an interview.

The cops question Kaulana and Levi. Levi tells them it was bullshit. “This wouldn’t have happened if the dumb haole [foreigner] never cut the gate. Typical haole thinking he owns everything, come down with a lot of money, try – try and fucking own everything, try to change everything up in Kahakuloa.”

Chris leaves Maui fuming. Back in Arizona, he hires a team of lawyers, involving multiple firms, to file suit against not only Kaulana and Levi, but the entire Maui police department. The villagers can’t believe they are being sued for defending themselves. Grandpa passed away shortly after.

The case dragged out for five years. In the meantime life kept going in Kahakuloa. The roof of the old church finally collapsed and so Kaulana, a carpenter by trade, got busy gathering community support and donations to rebuild it from the ground up. The case against him and Levi was nearly dismissed in 2019 when a plea agreement was reached in which nearly all the charges were dropped. Levi and Kaulana got a few years probation and credit for time served.

Chris was at the sentencing hearing, he’d flown back hoping to see the fires of hell fall upon the two men, now nearly 30. He even brought to court a shovel resembling the one that had been grabbed during the fight and asked the judge to hold it. Kaulana and Levi both took the opportunity of the unexpected face-to-face to apologize to Chris. Still, when they got their sentences, Chris was beyond himself. “This is not justice,” Chris told the judge, “I feel like the only person in the United States of America who cannot go back to his own home because of the color of his skin.”

Both Kaulana and Levi walked free that day. Kaulana went on to have his first child. Chris never moved to Hawai’i. And I dearly wish that this was the end of the story.

The video

Chris was expecting trouble before he even showed up in Kahakuloa. Unknown to the villagers, Chris was in fact the new owner of Preston’s uncle’s dilapidated old house by the ocean, as somehow he’d bought it online, sight unseen for $175,000. Even the police were highly suspicious because everyone knew about that old house, it was considered unsellable because Grandpa built it for his son and both houses shared the same gates, same driveway, and same water connection. Nothing stood there when Preston was growing up, it’s where they kept the pig pens. The bank had foreclosed on it more than a decade ago and no one had heard anything about it being sold to a rich guy from Scottsdale.

Chris knew how his arrival was going to look: a white guy showing up in a native village, but he didn’t have time for that. Chris knows the stories of violent natives. America was founded on stories of violent natives. So when he was packing up his luxury truck to ship from Scottsdale to his new island house, he installed cameras all over it. He also packed two guns.

The cameras recorded the fight. There is no video evidence, however, of Chris running his truck into the gates, blaring the horn, yelling at villagers, repeatedly cutting the locks, or pulling a gun on Grandpa. Isolated from the context (context that convinced the jury that Chris was not in fact targeted due to his race) the video looks bad. Kaulana and Levi are furious and it’s not clear why, they are just two violent natives. The day following the disappointing sentencing, Chris decides to seek revenge in the court of public opinion. He leaks the video to the press, again saying he is the victim of a hate crime.

When Hawai’i News Now published the video on their facebook page in October of 2019, it got over a million views in the first day.7 Though the details of the fight are not visible and much of the audio is intelligible, captions have been added to persuade the viewer. The internet exploded with accusations of anti-white bigotry. Weeks later Trump’s DOJ launched a federal investigation into Kaulana and Levi.

“In an unusual move, the U.S. Department of Justice sought to prosecute Alo-Kaonohi and Aki and secured a federal grand jury indictment in December 2020 charging each with a hate crime count punishable by up to 10 years in prison,” reported the AP.8

Kaulana and Levi were indicted in January 2021 when they were rearrested without bail and held until a new trial began three months later. This time around the old friends got no sympathy, their local lawyers were no match for the feds. In late 2022, eight and a half years after Chris first rammed the gates and cut the locks, both Kaulana and Levi were convicted and sentenced with hate crime enhancements. Levi and Kaulana, now in their mid 30’s, are serving 50 and 78 months, respectively, and are expected to begin paying Chris Kunzelman a sum of $25,000 in restitution upon their release, through monthly installments.910

“They were made an example of, even the news reporter said that, even the district attorney said it. They were made an example of,“ Preston laments. News outlets ran header images of an injured white settler in between two violent natives. Kaulana and Levi were used as examples of what happens to those who resist take over, which Americans tend to agree on across party lines. Yes, the Trump Justice Department wanted something to throw supporters that believe in the conspiracy theory of white genocide, but the Biden-appointed Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clark would be the one to try the case to completion. Speaking about the hate crime enhancements, she said, “The jury’s verdict – and in fact this whole prosecution – reflects the Department of Justice’s commitment to protecting every person in this country from race-based violence, regardless of the race of the perpetrator or the victim. The law applies equally to everyone.”11 She is Black.

The crime of hate

Much of the Kahakuloa case obsessed over the word haole, which Hawaiians, scholars, and courts have agreed is not a racist term. It means foreigner or outsider but many white settlers in Hawai’i have felt personally attacked when they are accurately described as being an outsider. According to court documents made public by National Indian Law Library,12 Levi called as an expert witness a native scholar from the University of Hawai’i to explain the history and use of the term haole, proving that it was not racially motivated. While she was allowed to testify about the unique culture of Kahakuloa, the government excluded her testimony that “the contemporary use of “haole” can never carry an offensive or derogatory connotation,” ostensibly because settlers are offended by it.

Hate crime enhancements serve to more severely punish otherwise illegal behavior. They are applied under the Shepard-Byrd Act, which Congress passed under their powers given by the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish “all badges and incidents of slavery.” Its original use targeted hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan, but its contemporary use, ironically, often also protects against alleged anti-white hate crimes, playing into the false theories of white genocide. When two young native men defended their village from an arrogant armed settler, the settler suffered a badge of slavery. After Kaulana and Levi’s convictions, articles discussed “Hawaii's complicated race relations”, explaining the modern impacts of settler colonialism while hand wringing about its outcomes, normalizing settler violence and making a spectacle of native violence.

The defense argued plainly that “depriving a white citizen of something simply is not a badge or incident of slavery or involuntary servitude.” Yet the higher courts disagreed. “U.S. District Judge J. Michael Seabright said the attack is different from other hate crimes, such as going to an African American church and shooting or targeting a nightclub full of people from a certain ethnic group or sexual orientation,” reported the AP.

This is actually untrue. According to the FBI’s statistics on hate crimes nationwide white people account for the second most hate crime victims, making up 1 of every 6 targets, a ratio consistent in Hawai’i.13 Of course, this is misleading because the very nature of hate crime enhancements is that they require litigation to prove their existence, rather than a crime that a person can be charged with outright. In other words, white people have won the second highest percentage of cases involving hate crimes, reflecting the systemic imbalances of the justice system.

“After a hate crime has been perpetrated, unless they catch the perp, prosecute and then go to trial and they actually use the enhanced sentencing, nothing gets transmitted up to the FBI,” Michael Golojuch Jr. from Pride at Work Hawai’i recently told Hawai’i Public Radio. “If they catch the perp and they do a plea deal, it's not considered a hate crime.”14 The Kahakuloa case is no different from the contemporary use of hate crime statutes to frequently punish people alleged of committing anti-white crimes. To suggest otherwise is to singularize Kahakuloa villagers as especially hateful, which they are not.

I technically told this story backwards. There have been dozens of articles over the last decade of trials and they all follow the same script. Two natives brutally (i.e. like brutes) assaulted a white man because Hawaiians are violent and hate foreigners. Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke called the hate crime verdict “justice and vindication to the victim, a man who was assaulted and nearly killed simply based on the color of his skin.”15

Fortunately I am not required to follow the settler-centric script. I have the privilege of being able to repeat what Hawaiians themselves are saying. “He didn’t come there to live, he came there to be the boss,” Preston insists.

Further, I know the type of rich American who settles Hawai’i: arrogant, entitled, and unaccountable. I know the type of rich American who settles Hawai’i because they are the same type of rich American who settles Puerto Rico.

The Haoles of Humacao

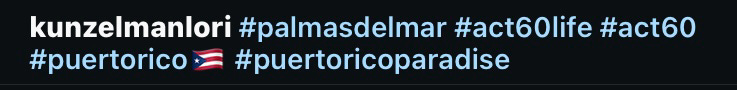

Chris and his wife Lori decided not to move to Hawai’i after all, they say they don’t feel safe. Still, they insisted on their tropical home away from home. So instead they moved here, to Puerto Rico, to a historically-Black town named Humacao, in a majority-white gated community called Palmas Del Mar.

Palmas del Mar is its own world. Behind the gates and guards, this miniature city is built on 2,750 acres, has 25 neighborhoods, and is complete with a bank, retail shops, a private school, 16 restaurants, 20 tennis courts, a country club and beach club, and a hotel. Like Kahakuloa, much of Humacao has long been a small fishing community. The Palmas private beach—when all beaches in Puerto Rico are supposed to be public— takes shoreline from locals.

When the electricity goes out for the rest of Humacao the people of Palmas have light. When the water is rationed for the rest of us, the pools of Palmas stay full. It’s a walled-off haven for rich settlers, and many of the condo owners are here on Act 60 terms, a tax evasion scheme that specifically targets rich foreigners who want to keep up their life in the states but avoid their tax obligations, simultaneously ripping off both the people of Puerto Rico and their home state.

In Puerto Rico, the Kunzelmans found paradise where they could finally live stress free. When Humacao police arrested the couple for “a pattern of abuse” against their 14 year old daughter (a remarkable feat inside the gated community) they easily paid both $10,000 fines.16 Chris smiled in his mugshot. The pair continues to occupy Humacao for at least half the year, between returns to Arizona and resort-hopping throughout Latin America. Chris still explores; he went to 16 countries last year alone.

Chris and Lori found it easy to settle Puerto Rico when the Hawai’i plan fell through because it’s all the same to a settler. In a show of settler solidarity that’s almost too on the nose, Lori’s facebook banner is an American flag blended with an Israeli flag.

As for the house in Kahakuloa, they still own it. Despite remaining unsold and off the market since Chris bought it, the house is currently assessed at over $311,000, nearly double his original investment. The property taxes have thus doubled as well, which will ripple throughout the village. This was his plan all along, and there is no promise that he won’t be back.

His presence here in Puerto Rico makes me reflect on the same culture of resistance, passed along throughout the generations. How long until every “Gringo Go Home” on the streets of Santurce is treated as hate speech?

Meanwhile, Kaulana and Levi, who immediately appealed their convictions, still have years on their sentences, despite local efforts to bring their cases to wider attention and clear their names.17 Kaulana’s toddler will be in middle school when he gets out. If Kaulana was out today, I imagine he would be alongside his little brother rebuilding houses down in Lahaina.

The 2023 fires that tore through the historic town came within two dozen miles of Kahakuloa, shutting down the highway that connected the village for months. Preston sees the slow pace of the recovery efforts as intentional—another way to push out locals.

Lori admitted she was unaware of the history of Hawai’i before deciding to move there, but said “attacking an individual white man doesn’t change history or improve things or justify actions on anybody’s part.” I disagree. History was changed on the eve of Valentine’s Day, 2014, and justification depends on morals, which are often different for the native and the settler.18

James C. Scott, the late Yale professor who the New York Times named the ‘unofficial founder of the field of resistance studies’,19 called such individual acts of defiance and defense the “weapons of the weak”. Individual acts make little change, but together they offer a form of collective self defense. “Everyday forms of resistance make no headlines. But just as millions of anthozoan polyps create, willy-nilly, a coral reef, so do the multiple acts of peasant insubordination and evasion create political and economic barrier reefs of their own.”20

This is how the powerless make their political presence felt. “And whenever, to pursue the simile, the ship of state runs aground on such reefs, attention is usually directed to the shipwreck itself and not to the vast aggregation of petty acts that made it possible,” Scott wrote.

Preston and I have traded theories about why Chris did it. Why did he show up that way? Why the lawsuits and why the media circuit? Preston suspects that Chris bought the house under shady conditions and then sought to pressure the family into capitulating to his demand. I can see the possibility, but I’ve not been privy to all the information Preston’s witnessed. I tend to think that he was just an arrogant settler who rarely considered accountability and once some native kids stood up to him, he wanted them lynched. Settlers become uncomfortably self aware when they realize they are in the home of natives, even the guy from Nat Geo Traveler wrote that Kahakuloa made him feel paranoid, so he quickly passed through.

White America really empathized with Chris’ fear, feeling their own settler status equally threatened. The Kahakuloa case was a shot across the bow of all communities willing to resist modern conquer. The chorus of media that followed the script amounted to extrajudicial punishment. It served to remind everyone that America will protect its settlers when the time comes to push into the next frontiers. The processes of take over, settlement, and displacement of the Kingdom of Hawai’i have never been as complete as statehood implies.

Preston tells me that every island of Hawai’i is different, that every single island in the Pacific is culturally unique. Now that wide array of culture is disappearing and the people in charge are letting it, “it’s so blatant, it’s so obvious what they’re doing. And I know I sound paranoid, and this is my opinion, I see it. You can see them raping it. Look at Lahaina.“

“People, just like Puerto Rico, are leaving their homes. Generations of people who know the culture,” he paused.

“Oh shit, excuse me.” I could hear the Army veteran fighting back tears. “You know, generations of people are leaving and they’re probably not going to go back. So what’s going to happen to our land now?”

I recognize the pain. All I muster in return is “it’s scary.”

“It is very very scary,” he replied. “All those memories. The stories that are passed on from generation to generation. The land, the fish, the people, gone, just like that. All for what, money? That’s what we’re trying to protect. That’s exactly what we’re trying to protect,” he continued.

“We try to keep people away, not violently you know, we’re just trying to keep people from taking that. And it’s always been that way, since I can remember. If we don’t slow things down, Kahakuloa is—we’re going to lose it,” Preston fears. “One way or another somebody’s gonna find a loophole. Like this guy.”

There was a back and forth during the fight that deserves more analysis than the use of the word haole. While still verbally trying to get Chris to leave, Levi tells him “you don’t belong here”, to which Chris shoots back “I do belong here”, and Kaulana follows up with “no you don’t.” They are saying opposite things, but both sides are accurate. To the kids, Chris did not belong to Kahakuloa; he did not care for the people, he knew nothing of the fish nor the whales, he’d never weeded the taro patches or watched out for the night marchers, he did not belong to the community. To Chris, however, the old house belonged to him; the charge cleared his bank and now this chunk of Kahakuloa was his belonging. To the courts, this was no miscommunication, it was yet another moment of the unwarranted anti-white hatred that Chris experienced that day. The issue clearly was never about race.

Most of the family didn’t want to discuss the case, they say the nightmare is almost over. It’s gone on for eleven years and only has six left, plus the years of garnished wages after they get out. It’s impossible to know if this story will help Kaulana and Levi because the damage has already been done. Preston says Chris desecrated his home and destroyed generations of hard work with the way that he painted Kahakuloa to international media. Even if someday the two are released and expunged, people will still remember those violent natives.

That is, unless we tell this version of the story, of all stories, enough times and in enough ways to create that collective barrier known as resistance.

Quieren quitarme el río y también la playa,

Quieren al barrio mío y que abuelita se vayan,

No, no suelte' la bandera ni olvide' el lelolai,

Que no quiero que hagan contigo lo que le pasó a Hawái.

Hiraishi, Ku’uwehi. “Context for Maui hate crime ruling includes complex history.” Hawaii Public Radio. March 9, 2023. https://www.hawaiipublicradio.org/local-news/2023-03-09/context-for-maui-hate-crime-ruling-includes-complex-history

The size of the village is mentioned in this story about Kaulana rebuilding the village church. “Volunteers rebuilding Kahakuloa Hawaiian Congressional Protestant Church. Lahaina News. May 10, 2018. https://www.lahainanews.com/news/local-news/2018/05/10/volunteers-rebuilding-kahakuloa-hawaiian-congregational-protestant-church/

McCarthy, Andrew. “Maui: Is There Anything Left to Discover?” National Geographic Traveler. March 2010. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/maui-traveler

Chris Kunzelman 2025 interview with Ben Richardson for Not Normal Network. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5XGyf52ANXQ

Kunzelman et al v Scottsdale, City of. 2010. https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/4132943/kunzelman-v-scottsdale-city-of/

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v KAULANA ALO-KAONOHI AND LEVI AKI, JR.,https://www.justice.gov/d9/2024-02/u.s._v._alo-kaonohi_and_aki_nos._23-373_23-416_23-635_9th_cir._02.14.24.pdf

Daysog, Rick. “Victim of Maui beating criticizes authorities for not pursuing hate crime charges.” Hawaii News Now. October 19, 2019. https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2019/10/19/victim-maui-beating-criticizes-authorities-not-pursuing-hate-crime-charges/

Kelleher, Jennifer Sinco. “A hate crime lays bare Hawaii’s complicated race relations”. Associated Press. March 3, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/hawaiians-hate-crime-beating-sentence-55d0a9d504a49b062f56c1d09e662fd8

Kelleher, Jennifer Sinco. “Maui men imprisoned for hate crime beating to pay 25K.” The Maui News. April 6, 2023. https://www.mauinews.com/news/local-news/2023/04/maui-men-imprisoned-for-hate-crime-beating-to-pay-25k/

“Two Maui Men Sentenced for Racially Motivated Attack on White Man.” US Department of Justice Press Release. March 3, 2023. https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/two-maui-men-sentenced-racially-motivated-attack-white-man

“Two Men Convicted of Hate Crimes for Racially Motivated Attack on White Man”. Press Release. US Department of Justice. November 22, 2022. https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/two-maui-men-convicted-hate-crimes-racially-motivated-attack-white-man

National Indian Law Library. Indian Law Bulletin, Federal Courts 2022. https://narf.org/nill/bulletins/federal/documents/us_v_alo-kaonohi.html

“FBI: 120 Hawaii hate crimes recorded in the past 5 years”. Associated Press. September 7, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/crime-hawaii-honolulu-hate-crimes-907a55497f9aeede54b0648ad577f7e6

Caries, Emma. “Bill seeks to gather more accurate date on hate crimes in Hawai’i”. Hawaii Public Radio. March 3, 2025. https://www.hawaiipublicradio.org/local-news/2025-03-03/bill-seeks-to-gather-more-accurate-data-on-hate-crimes-in-hawaii

Fujimoto, Lila. “Probation order in shovel attack.” The Maui News. October 18, 2019. https://www.mauinews.com/news/local-news/2019/10/probation-ordered-in-shovel-attack/

“Una pareja enfrenta cargos criminales por un alegado patrón de maltrato contra su hija” El Vocero. https://www.elvocero.com/ley-y-orden/justicia/una-pareja-enfrenta-cargos-criminales-por-un-alegado-patr-n-de-maltrato-contra-su-hija/article_cc1ff194-4893-11ec-950a-af3a6b7b0896.html

“Public presentation questions sentencing of men convicted in West Maui hate crime.”Hawaii News Now. July 6, 2023. https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2023/07/06/public-presentation-questions-sentencing-men-convicted-west-maui-hate-crime/

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. François Maspero. 1961.

“James C. Scott passed peacefully in his home in Durham, CT on July 19, 2024.” Yale Universty, Department of Political Science. July 23, 2024. https://politicalscience.yale.edu/news/james-c-scott-passed-peacefully-his-home-durham-ct-july-19-2024

Scott, James C. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. Yale University Press. 1985.

You’ve managed to put into words the feelings that have had me in tears over the continued invasion of Puerto Rico and other indigenous lands. This is beautiful, solid storytelling and perspective. Thank you for writing this.

Incredible reporting Steven. Just wow. Sharing with everyone I know.