The Pee Plantain and Endless War

Farmland, worldwide, has been on a course of destruction for millennia, dramatically expedited by the mining of fossil fuels and the destruction of communities.

Plantains in Las Marias that were blown over after a minor storm in spring 2022. By Steven Casanova

There are huge banana plants1 that line our farm’s perimeter, planted decades ago by ancestors of the community. The center of the farm was left open for the king cash crop - coffee - but the ancestors knew that bananas would always provide food, even when the coffee didn’t buy bread. Five years ago Hurricane Maria slammed into our town of Utuado at nearly 200 mph and tore the entire cash crop from the earth to such an extent that the landowner decided to just bulldoze the whole farm and start from scratch. Bananas, and their cousin the plantain, ensure abundance. Once established, they become permanent clumps that only need to be kept clean of vines and then harvested before the rats do. A single banana rack commonly has around hundred bananas and weighs nearly thirty pounds. And the ancestors planned wisely; with the cash crop all gone, and no cash to harvest, toxic weeds and intense grasses blanket the farm now, but the banana clumps remain. Some tower eighteen feet tall and produce racks of food monthly. Their survival illustrates farming’s duality, a balance between the realities of our food system: abundance and war.

Utuado is world famous for its landslides. After Maria, the reports that got out to the U.S. and beyond told how people were trapped after thousands of landslides blocked roads in every direction. After Fiona, just a few weeks ago, the world saw us lose the main bridge that led to our university. There are two reasons for landslides that damage infrastructure. One is that the infrastructure never should’ve been there, in that form; when the U.S. installed a hydroelectric dam in Utuado in the 1940s2, it flooded entire towns3, pushing people into the steep and fragile mountains, connected by roads that are built across occasional waterfalls. And the other is that the land has lost its forests, its trees that gripped the Earth with deep roots and also removed water from the ground through evapotranspiration, in order to plant endless acres of cash crops. Utuado isn’t a rainforest by USDA standards like El Yunque, but its annual rainfall is only a few inches shy of the qualification. So, when rain saturates the land and the weight becomes too much for the bushes to hold, the earth falls, buries, topples, and collapses. These two root causes- human displacement and reckless land use- have repeated themselves for centuries on our farm, like cycles of war and reconstruction. War, of course, is a principle author of history, as is, though less credited, erosion.4

This was once a coffee mountain. Trees were cut to plant thousands of coffee bushes. Trees were cut to make room for oranges, chirongas, and grapefruits, to grow shade coffee and produce a second income. Trees were cut for roasting coffee. Trees were cut to make space, houses, and fuel for all the people who worked the massive coffee mountain. Forests were eliminated because it suited the markets of the colonial power.

Now we live on a clay mountain. The world’s coffee addiction robbed Utuado of its topsoil, shipped across oceans or carried down river to the lake created by the dam. But the agricultural industry was never based on the merits of Puerto Ricans, and so when foreign imperialism found places to exploit even more efficiently, all those people who once tended the land were forced to leave. They migrated into the cities or afuera.5

An example of the pure clay of our farm. This extreme example is due to heavy machinery and subsequent erosion. By Steven Casanova

The farmland that is left is acidic, barren clay with only a thin film of organic material, densely thicketed with thorny bushes and vines - not the most ideal place to grow food6. Yet, the whole region is farmed. This story, with countless variations, exists throughout the Global South/Third World/developing/underdeveloped/low income countries7, or more precisely: nations and lands that have been relentlessly extracted from to drive European and American economies. Or even more precisely: land that was stripped of its nature, which by the European definition included the Indigenous people and original caretakers, in order to pursue profit by any means necessary8.

The 20th century response to these generations of endless extraction came in the form of the Green Revolution, which brought major changes to agricultural communities in the poorest nations of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The National Academy of Sciences explains the era as “an extraordinary period of food crop productivity growth…despite increasing land scarcity and rising land values. Although populations had more than doubled, the production of cereal crops tripled during this period, with only a 30% increase in land area cultivated”.

The Green Revolution focused on new varieties and cultivation methods for corn, rice, and wheat, and is widely remembered as an unparalleled success in reducing hunger and poverty. So much so, that, as the N.A.S. puts it, the world is preparing for a new Green Revolution, especially as concerns rise regarding “sustaining productivity gains, enhancing smallholder competitiveness, and adapting to climate change”9. These trends are worth paying attention to, and it is important that we situate this moment in its proper place in history.

“Map of Puerto Rico Showing Distribution of Crop Lands, 1899.” By Herbert M. Wilson. This was created immediately after the U.S. takeover of Puerto Rico.

Since the earliest days of colonization Puerto Rico has been chopped up by its extractable goods. The flat coastal lowlands were cleared for sugar, the midland hills plowed for bananas, oranges, and tobacco, and the mountains reshaped for coffee. These became the roots of ongoing segregation as enslaved African people were trafficked for the more difficult and often deadly labor of industrialized sugar, while poor Europeans could be lured to the hills and mountains to be paid minimal wages for the mind- and hand-numbing work of picking coffee and rolling tobacco. Africans that remained on the coasts after emancipation were pushed to the infertile flood zones at the edge of the ocean. Today, Airbnb is displacing their descendants in order to get beach front property.10

The sugar boom was short lived in Puerto Rico11, it began after enslaved peoples liberated themselves and created the first free republic in America, Haiti, next door12. Enslavers fled Haiti and tried to keep the business going here. Especially as the Haitian revolution led to the many wars for Independence from Spain throughout Latin America, Spain doubled down on their Caribbean cash cow, boosting and then keeping afloat the industry through tariffs, land grants, and ever harsher labor laws13. But the combination of sugar’s heavy nutrient demand and the unsustainable rate of plantation development made possible only through enslaved labor, was destined to exhaust the soils despite colonial desires.

The Green Revolution wasn’t universally applied throughout poor and hungry nations, it was strategically used to quell rebellion. The initiative was conceived in the 1960’s as a capitalist counter to socialism’s Red Revolutions. Instead of promising food for hungry people via land access, it promised food via fertilizer access, genetically modified crop varieties, and neoliberalism. Production climbed and prices dropped, profits were traded in the cities and abroad. Someone had to pick this expanded yield, albeit at a lower pay rate than before. The real legacy of the Green Revolution was to squeeze land and land-working peasants more efficiently while promising abundance to the cities. As Raj Patel explains in his book A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things, “The long Green Revolution… did not reduce hunger. [Excluding China, the global] ranks of the hungry swelled by more than 11 percent over the course of the Green Revolution. And while reporters are happy to celebrate the fact that ‘India’s wheat production doubled from 1965 to 1972’ and rose steadily throughout the 1970s, the amount that Indians actually ate hardly improved over the same period”. Likewise, the increased wheat yields in Mexico still receives accolades, yet wheat was virtually nonexistent in the Mexican diet before and immediately after the Green Revolution transformed their lands14. The N.A.S. admits that in the poorest areas of the world which rely on rainfall and cannot afford to build irrigation systems, the Green Revolution actually did not reduce poverty or hunger, and instead expanded wealth gaps. As farms have been pushed beyond their capacities and their topsoil continued to be exported wholesale in the form of commodities, the Green Revolution responded by sending fertilizers, GMOs, and compact farm machines around the world in order to keep crop yields just above revolution-level. A new iteration of the Green Revolution threatens to once again ramp up pressures on small farmers and peasant farmworkers to take on the brunt of the problems facing the workers of the cities and First World/Western Countries/Global North/developed nations: food price inflation, supply chain monopolies, and climate change.

So when we moved here we came with all of this in mind. We are on this land because it is no longer viable for other people to make a living from farming here. Centuries of colonial war has deprived the people of economic value just as equal time of war on the land has robbed the land of its natural value. A forty-pound rack of bananas, raised for nine months in degraded soil, harvested and hauled to town, might sell for $8 on a good day. It requires a pick up truck completely full of bananas, ass nearly scraping the street, to make $200, a teenager’s weekly pay at McDonalds. The fruits of twenty five bananas trees would be necessary, and a farmer would need to maintain 1,500 banana trees to sustain that minimal weekly pay - an unbelievable amount of work. Instead, it makes more sense to farm coffee for people around the planet, rely on the store for an imported grocery supply, and use chemical fertilizer to counter the affects of soil degradation and a destroyed labor market. We are living in the Green Revolution’s neoliberal nightmare.

Last August we met a man named Hector selling a truckload of plantain seeds for $75. (Explanatory common for people afuera: plantains are no longer grown from true “seed”. They’re cloned from sprouted rhizome cuttings, hijos, which are anywhere between six inches to a foot and a half in size, when cleaned. It’s common to see three or four hijos coming off the parent plant. These can be harvested and moved to start their own clumps. These clumps are permanent and will continue to produce staple carbs for the rest of our lives). Hector responded fondly, as most elders do, to learning that Alex (AlexMatzke.substack.com) and I are some young farmers. He knows too well that it’s barely a viable career anymore, but also that the loss of farmers doesn’t just impact the economy - it’s the fate of our food system on these small islands so controlled by distant lands15. Hector tried to kick us some game, “Plant them eight feet apart. These aren’t guineos, they need the sun.” And he not only told us how they should be fertilized, he showed us the bucket of salts (ammonium), gave us the price, and told us where to buy it and how to use it (convert it to ammonia). “Mix this, one cup to a gallon of water, and soak the seeds in it overnight before you plant them so that they can grow good roots. It’s about a hundred bucks these days, but it’s worth it.” He could sense my hesitation and he insisted, “if you don’t, they won’t grow.” Standing in the shade of massive plantains that grew across the entire horizon, there was reason to believe he knew what he was doing.

115 plantain cleaned hijos loaded into the back of our truck. Photo by Alex Matzke.

Hector wasn’t the first, nor the last, person to present to us farming and chemical fertilizing as one in the same. It’s the way things have been forced to be for generations, and Hector knows that any threat to yield is a threat to the family keeping the farm. He was telling us how to survive this game. But what is equally concerning to us is that, while we have no doubt that fertilizer would produce fat plantains, it would do nothing to support the life of the land. In order to have a crop we’d have to become dependent. And if that $100 bucket gets more expensive, we’d have to pay, whatever the price. We hope to grow enough food to give away all the surplus, only selling when absolutely necessary, but buying fertilizer guarantees that we need a strong foothold in the profit rat race to grow anything. It’s an incredible privilege to even think about putting anything before profit. And it’s not hard to find an elder talking about life “when the boats stopped coming”16. Imported fossil fuel- based fertilizer is as unsustainable as it gets in a colony. We cannot rely on U.S. politics to feed our community, we need the land to support us. But I have never seen crops grow directly into clay like ours, pure enough to be used in art class. So, in order to figure out just how much work needs to be done, we decided to start with an experiment.

We cut through the thicket and planted 115 plantains along contour lines17 across the face of the mountain, from the barren ridge into the forests that edge the parcel. These contours will eventually become terraces, once roots have been established. Each plantain seed got a bit of manure and nothing else. We did not till the land and will not irrigate it18. This way we can see just how much life the farm can support, if any, and how the different micro climates affect crops19. We knew that even in the worst case scenario at least two of the 100+ would survive, produce up to $40 of fruit, and we could use the hijos to expand to more clumps next season. But that in the best case scenario we would have a truck full of food to bring around to folks in just nine months.

We used a simple homemade A-frame level to mark contour (level) lines. Here Alex is burying the plantain seeds. Photo by Steven Casanova.

In a year, a healthy plantain towers fifteen feet tall, produces twenty pounds of plantains, multiple three-foot hijos, and has roots that span out ten feet long. Following our plantain line towards the forest, they get taller, fatter, and greener, illustrating how the trees are repairing the soil through their leaves and root networks. But out on the ridge, with the thorns and vines, the plantain roots can’t break through the hard clay more than a couple inches, and as far as they can grow, there is no nutrition there for them to find. It’s been a year and the majority of our plantains have never grown more than two feet tall. Our neighbors apologize for our embarrassing plantains in a hushed, sorrowful tone, “Such a shame the platanos never grew.” When telling their friends about us, they describe our farm as “organic,” with a sigh. We get it, who can bother with experiments when there are mouths to feed?

Since planting, we’ve collected many different natural inputs for the farm - leaves and rotten wood from the surrounding forest, wood ash from the fire pit, eroded soil downhill from our neighbor’s chicken coup, horse manure from a few towns over. We’ve been piling it all onto the highest terrace on the farm so that erosion feeds the crops below20. We also plant legume trees which bring nitrogen into the root ecosystem. All of it will slowly help repair and replenish the topsoil over some years but really won’t do shit for this year’s harvest. So a few months ago we started another experiment using natural, fast release, liquid fertilizer with instant results.

Ammonia has been naturally derived from plant and animal decomposition for centuries. It has also been produced from processing bat and bird manure, guano. Ammonium is a salt that can be mined from deserts and is the starting point for making most components of synthetic fertilizer. Hector used it to make ammonia, but it can also be processed to make a synthetic version of urea. Ammonia, ammonium, and urea are all different forms of nitrogen which are widely used in agriculture and have both natural and synthetic sources.

On our farm we are using the most bio available source of ammonia we have access to, independent from politics and fuel costs - our own pee. Its not a novel idea, its long been part of the human relationship to the rest of nature as agriculture was developed. Pee is full of different nutrients that plants can use, particularly a ton of nitrogen - crucial for new green growth. Mixed with another waste that came alongside human settlements - wood ash - and crops essentially have all that they need21.

I began with two very sad plantains, eight feet apart like Hector said, in the same soil and same conditions. At six months old they both still looked like one month old: a foot tall, the same four leaves, no new growth. The plants used up the manure as they got established and then hit an impenetrable clay wall. I left one alone as the control, while the other became The Pee Plantain.

The Pee Plantain sending out a new leaf. Photo by Steven Casanova.

We have lived without plumbing for nearly a year now22. If we reuse the same pee spot enough times, the grass and weeds grow more vigorously and their color gets richer. So once The Pee Plantain was named it became the ritual spot and the results seemed instant. A fifth leaf shot out the center, twice as big as the rest, then a sixth. The whole plant was a foot taller and notably fatter in weeks. In a month The Pee Plantain had more than doubled in height, now sporting eight big, dark green leaves. As the plant doubled and doubled again, we added the wood ash, manure, leaves, rotting wood, and clay soil, until it now stands twelve feet tall with four healthy hijos, the tallest of which is twice the height of the original plantains. The control plantain has still not budged an inch.

In 1908, German researcher Fritz Haber developed a method of using high-temperature and high-pressure industrial chemistry to react hydrogen (from petroleum or natural gas) with atmospheric nitrogen to produce ammonia. He worked with engineer Carl Bosch to solve mechanical problems to better commercialize the reaction and on October 13, 1908 they patented the Haber-Bosch process of creating the source of life out of thin air - and lots of liquified fossils. Worldwide population growth soared after this moment when we started eating fossil fuels.

The New York Times ran an article a few months back talking about the usefulness of pee fertilizer, how hobbyists in New England were collecting it to lower their waste, the ways families have used pee fertilizer in rural West Africa for generations, and how liters of pasteurized pee can be casually purchased there like water or fuel23. This article was run after the beginning of the war between Ukraine and Russian as fertilizer costs have gone up globally. The two countries are the main producers of synthetic fertilizer, and they’re also global leaders in extracting fossil fuels, and so when they decide to keep their supplies to themselves, farming communities worldwide suffer.

I told my mom about this article, hoping that introducing the concept through the New York Times might lessen how gross she found it. To my surprise, she told me about another article she’d found through Facebook that also praised the power of pee-fertilizer. To even greater surprise, that article said plainly that while urine from men is great for the garden, urine from women is full of dangerous hormones. Yes, some sexist pseudoscience, but left unchecked, it can be convincing and ultimately harmful. Since beginning the experiments, Alex and I have both expanded to multiple Pee Plantains, pee papayas (pee-payas), pee tomatoes (pee-matoes), and pee yautias (yau-pee-a’s) with the same great results. Facebook is a trip and getting into patriarchy and farming will require its own articles.

The Pee Plantain has helped me reevaluate my ideas of waste. Alex and I talk about this all the time; her seminar-like class, aptly named No Such Thing As Trash, pushes art students to contextualize their work in the realities of colonialism. It’s a necessary practice for all people benefiting from colonialism, which is based on assumed access to land to be used for extraction, creation, and inevitably the discarding of waste that is produced24. Rather than waste being considered pollution to be thrown away, we must acknowledge that there is no “away”, that we are responsible for our waste, and that a proper re-contextualization both frees and demands of us to utilize byproducts rather than ignore so-called waste. After seeing the abundance of the Pee Plantain, I feel the only waste is the lost opportunity to use the pee that’s instead flushed “away” to cause harm elsewhere.

The results are shocking to see, honestly. The small, sad plantain is lodged in the same thick, dense block of clay as the towering Pee Plantain and its hijos, just feet apart. Clay is an incredibly useful growing medium because it retains water and has trace minerals lodged in it. But the heavier the clay, the less nutritious organic material, the more saturated clay becomes when wet, and the less air can get into the roots. It is precisely the urine that has encouraged the growth of the leaves, which in turn made it possible for the roots to keep pushing, and yielded a harvest where there would’ve been none to speak of. That is what makes the power of modern fossil fuel agriculture so hard to believe, land is barely a consideration anymore.

Growing crops without soil is multiple millennia old, just as is the wholesale depletion of topsoil. Hydroponics is the modern face of tech-meets-agriculture, though the term was coined a century ago. Hydroponic plants usually grow directly onto plain, inert clay pellets. But hydroponic plants require constantly moving (aerated) water and liquid fertilizer to make up for the clay’s lack of nutrients. Hydroponic rigs are, in concept atleast, small models of many big ag farms today. Industrialized agriculture has gotten used to nutrient-deprived soils, even come to prefer them.

Most tomatoes in the U.S. come from Florida and they’re the state’s second biggest crop. They are grown in soil that is barely different than the sand on Florida’s beaches - basically inert pieces of rock, albeit less salty than the beach - but with a synthetic fertilizer cocktail and underpaid (sometimes unpaid) farm labor the plants can yearly yield truckloads to the tune of $460 million dollars25. These fertilizers have yet to achieve the flavor or nutrition of the nature they’re mimicking, but that hasn’t slowed the boom in tomato accessibility nationwide and year round. Our neighbors grow their coffee fields in the same ways. From inert clay mountains they raise fat coffee bushes that bow over by the weight of plump red berries. Land is now just a growing medium to be doused in chemicals and turned to profit. So while regenerative farming is all the talk in corporate board rooms, on the ground, The Pee Plantain is considered nonsense.

Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch weren’t developing a way to chemically produce the source of all life with humanitarian motives alone. Germany, like much of Western Europe, had spent the end of the previous century amounting unreasonable fortunes by colonizing Africa through war and genocide26. The dramatic advancements in weapons made possible by industrial steel required an unimaginable amount of gunpowder. But through colonization, and now through chemistry, gunpowder could be turned to gold.

Raj Patel explains in a History of the World in Seven Cheap Things, “there were strategic imperatives behind their research. Guano, an important source of ammonia, had been mined prodigiously and been replaced by Peruvian saltpeter (sodium nitrate, NaNO3) from the Atacama Desert. This “white gold” was vital to the production of gunpowder and to soil fertility, and the British controlled its trade. The Haber-Bosch process delivered a substitute- one so significant that Haber won a Nobel prize in 1918” (at the height of the bloodiest war Europe had yet seen). “As it happens, Alfred Nobel had made his fortune in explosives, and Haber’s and Bosch’s work provided Germany with key inputs for TNT and gel ignite, which Nobel had patented. Their knowledge decoupled the manufacture of gunpowder from the extraction of resources from specific sites and allowed the production of weapons through the use of nothing but energy and air. More than one hundred million deaths in armed conflict can be linked to the widespread availability of ammonia produced by the Haber-Bosch process.”27

Admittedly, while our own urine is a powerful, natural alternative to fossil fuel fertilizer, we do not produce nearly the amount that would be necessary to grow acres of plantains with our pee alone. Our Pee Plantain, towering over its neighbors by virtue of valuing our waste, is a symbolic proof to the power of reconnecting ourselves with nature. That reconnection, or reinsertion, by necessity, means that we will never raise acres of plantains alone - that wouldn’t be natural. Nor would it be natural to expect plants to grown on urine alone. There is always a threshold where a dose becomes poisonous, and so during dry times we run our waste water over pee-fed plants so they aren’t killed by nitrogen burn. What is seen as a limitation by industrial agriculture can instead be seen as natural wisdom. The farther that we stray from this wisdom, the more work is required to sustain the unnatural growth - both on a farm level and a nation level. Unnatural growth is forever doomed to hit the barrier of nature, yet instead of listening to the wisdom, the response for centuries has been war.

Before the Haber-Bosch process of making the main ingredient of both mass life and mass death, wars were fought to acquire guano. The U.S. declared ownership of over a hundred islands in the 1850s in the Guano Islands Act, and still disputes ownership over such an island with Haiti.28 The islands were scraped clean of their resources one by one. Then there were the Saltpeter Wars which changed the borders of Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. But Haber and Bosch were able to bring the power of war into their labs, detach it from nature, package it up, and sell it to the world.

This is the paradox of imperialism: the progress, growth, and production is predicated on the destruction, extraction, and exhaustion. Death and abundance are not pitted as opposites, but rather sides of the same coin, as if we can’t have one without the other. The noble discovery of life is awarded at the height of the carnage of the First World War, which said discovery made possible. It is as if discovering the source of life, at the same instant, uncovers the source of death. This is the mythology inherent in U.S. expansion - that people must die so that the nation may live, and the Haber-Bosch process has only accelerated the long history of the U.S. arms race.

As Raoul Peck, the director of Exterminate All The Brutes, an incredible four-part film that fearlessly and necessarily recalibrates the telling of world history, explains, “The industrial development of firearms [played] an important role in U.S. colonization... As a war president, George Washington thought it unreasonable to rely on foreign weapons. With generous start up funds, lucrative long term contracts, and heavy tariffs on foreign imports, he literally jumpstarted the U.S. arms industry into becoming the world’s first arms manufacturer. The very first corporation established by the United States was the Springfield Armory in western Massachusetts, founded in 1777. It soon introduced standardized interchangeable parts and assembly line production, key factors in the take off of the industrial revolution in the U.S. and its establishment as a capitalist imperialist state. And having more arms allows more expansion. More expansion means more wars, for which you then need more arms. A profitable chicken and egg bonanza in a totally incestuous relationship between military, industry, and government.”29

Public artwork by Bemba (@bembapr) in Mayaguez. Photo by Alex Matzke. The caption reads: “How will we explain to future generations that ‘it was good for the economy?’”

And every factory needs a farm - a way to cheaply feed underpaid factory workers30. The vertical expansion of skyscrapers in the city requires the horizontal expansion of frontiers in the countryside. The two are integrally connected, a riff in one causes a response in the other, and the separation is often global. Nonetheless, the same war that prompted the need for expanded frontiers is used to keep the workers of that frontier in check. Like the banana plantation workers of Ciénaga, Colombia who were massacred along with their families, by the thousands, for going on strike in 1928.

Cheap synthetic fertilizer made it possible for United Fruit Company, now Chiquita, to expand its production on a global scale. United Fruit Company was a conglomerate of banana traders that merged at the end of the 1800s31. Latin America, like Africa, experienced an influx of European and United States trading companies in those years, which replaced the trading of enslaved humans with the trading of terribly underpaid, and sometimes again unpaid labor. This time, through political and military power, private companies and governments alike could reap profits in London, Berlin, and New York with even less investment costs than was required to traffic enslaved humans globally, and instead could exploit people from their own communities. In some cases, food produced in colonies were traded literally to pay for war in the colonizing powers. During the Second World War, the British repaid hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. loans partially in cocoa (the third largest export behind tin and rubber) shipped directly from the British-run colonies in Africa.32

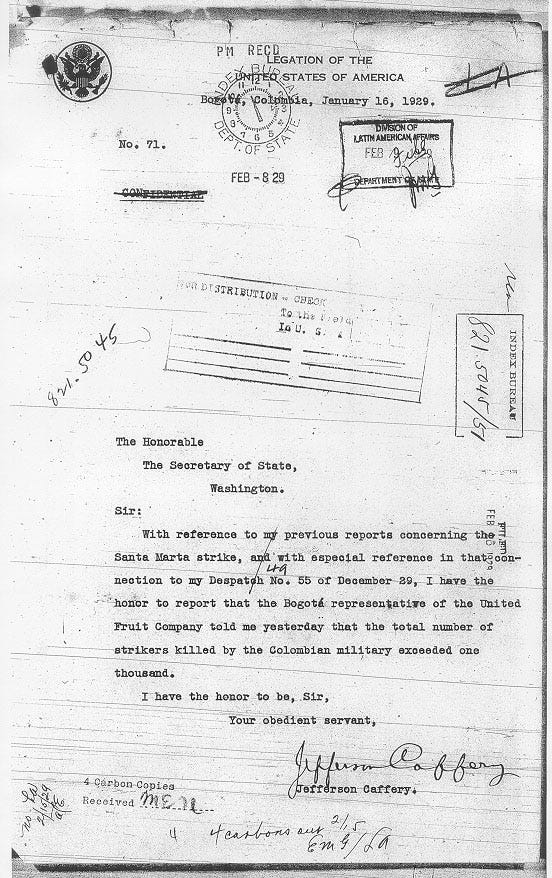

By the late 1920s the United Fruit Company had climbed toward what the company calls its ‘golden age’ and it enjoyed economic and political power across millions of acres in Latin America.33 The massive plantations again required cheap labor, often coerced of “independent contractors” trapped in company towns, and conditions were abominable. When Colombian banana workers stopped working for nearly a month to demand the end of obvious exploitation, it was a threat to the cheap food that U.S. industry depended on. United Fruit Company turned to the U.S. government, and telegrams between the U.S. embassy in Bogatá and the U.S. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg portrayed the strike as a communist threat. United Fruit called on the U.S. to threaten the Colombian government with military invasion and they had the leverage to cut off Colombia from the global banana trade. Caught between U.S. profits, the possibility of devastating war, and de facto sanctions (war by another name), it was the Colombian government that called the workers into the town plaza for a special announcement by the Governor and then ambushed the crowd with rooftop machine guns on all sides. According to State Department telegrams received by Secretary Kellogg, over a thousand Colombian men, women, and children were murdered on the Sunday afternoon known as the Masacre de las Bananeras34.

And that estimate is almost certainly an undercount, some estimates claim that upwards of 3,000+ life’s were taken, but exact counts are impossible because the bodies were dumped into the ocean. Barely three months prior to the massacre, Frank B. Kellogg coauthored an international peace pact, the Kellogg-Braid Pact, and compelled forty six countries to agree against using war as a means of advancing foreign policy. Secretary Kellogg received his Nobel Peace Prize the next year.

Food is a necessary factor left out of Peck’s chicken and egg explanation of U.S. expansion. Food is necessary to make weapons, which are used in the wars of imperialist expansion, in order to acquire more food, enforced by more weapons. The Haber-Bosch process is still used today to make both bananas and bombs in an endless cycle of control, detached from natural limits. Fossil fuels make this possible, and have been a principal factor in the decades of continued wars and plunder in the Middle East. As a result, the U.N. Is warning that Afghanistan faces the threat of losing upwards of fifteen percent of its population, six million people, to starvation this winter35. Whether the use of fossil fuels is phased out willingly in attempt to alter the course of climate change, the people make it impossible to continue their use by putting their bodies on the line, or they simply run out or become too expensive to extract, this status quo is not forever. War on the land and on the people inevitable causes apocalypses.

History warns, though, of what plundering nations are willing to do to survive and advance. Poor nations and peoples will not survive a remake of the tragic Green Revolution which leans even harder on the exploitation of people and land. The topsoil is already in the lake. Soil repair requires investment that does not yield immediate profit, and so is only possible when it does not come at the risk of losing everything. Some options for supporting this necessary labor include funding soil remediation, ensuring secure housing and land access, universal basic incomes, the end of exploitation of Black, brown, and poor people and nations and the payment of reparations to the victims of said exploitation, among many others. Without that support, modern industrial agriculture is at odds with the survival of the people doing the farming, and therefore, that of the entire world. Business as usual means that nations and peoples that have been robbed and are currently being robbed will continue to be robbed - unless massive resistance is met. This resistance may be the natural barriers that are rapidly being exceeded, or it may be people demanding the end to constant extraction, expansion, and exploitation. It is the difference between the Pee Plantain and endless war.

Hola! Welcome reader. Thank you for being here, and an extra thank you for reaching the footnotes and not giving up. Here I will give further context, explanations, and reading suggestions. The idea of doing footnotes differently came to me from Max Liboiron’s incredibly important book on doing science differently, Pollution is Colonialism. Go read it. They write with such clarity about issues that we must grapple with to be able to build anything restorative. But they also keep it real and I think about their writing frequently when working on my own. We are going to start with an easy note: bananas and plantains are the largest herbaceous food crops on earth - they are tree-sized but make instead of soft plant cells. So huge banana plant is redundant, but I am writing this for mostly people who do not live where banana plants can grow to maturity.

The Lago Dos Bocas reservoir was built in Utuado, in the center of the mountains, to supply electricity only for the coastal capital San Juan, 30 miles away. The access to and destruction of Utuado’s most fertile river basins was a mere side affect of electrifying the capital for the wealthy.

Technically they were not “towns” in the legal and political sense, but they were entire communities and economic centers established along the rivers. The factory smoke stack still shoots out above the water, and when devastating drought hits the area, the church steeple becomes visible.

While the official story of Columbus’ 1492 voyage to the Caribbean is that he was searching for shorter trade routes, it should be contextualized that the previous centuries of European wars and land degradation led to the transfer from feudalism to capitalism, and the fate of this new structure would depend on exploiting other lands, and therefore it was worth betting on an idiot’s voyage across the Atlantic.

In some cases, Puerto Ricans left by the thousands to work those other lands, as was the case when 10,000 Puerto Rican farm laborers were shipped to Hawaii in the early 20th century and eventually becoming a major demographic there.

If you judge by looks alone, the area is rich with green vegetation. But common among tropic (and therefore colonized and exploited) lands globally is that 90% of the life is above ground, in the vegetation. The warm and wet climate encourages constant growth, but that fragile vegetation is misleading.

These terms are not actually interchangeable. Some are based on national GDPs and others on whether a country was on team capitalist or team socialist. But all are causally used interchangeably to refer to, as the most recent U.S. president termed them, “shithole countries.”

Raj Patel’s History of the World in Seven Cheap Things spends a considerable amount of time illustrating the tactic of making Indigenous African and American people a part of nature, rather than human, a distinction reserved for certain Europeans and simultaneously cheapening nature to be something that must be tamed or removed in pursuit of profit and power.

Pingali, Prabhu L. “Green Revolution: Impacts, limits, and the path ahead.” 2012 Jul 31. National Academy of Sciences.

Fuck Airbnb for this, for gentrifying all over the world, and for running its business on stolen and occupied Palestinian land.

Short-lived is in global comparison, but it was still a literal lifetime for far too many people.

Raoul Peck explains in the second episode of Exterminate All The Brutes, “Indeed… a particular group of Black slaves, men, women, and children would rise. In just ten short years, they would fight and create the nation of Haiti, the truly first free republic in America. The only revolution that materialized the ideal of enlightenment, freedom, fraternity, and equality for all.”

Figueroa, Luis. A. Sugar, Slavery, and Freedom in Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico. 2005. This book unashamedly tells the history of the human trafficking of African here and throughout the Caribbean. The story has been hidden, ignored, and heavily manipulated by the dominant culture and I appreciate Figueroa’s certainty in the facts and the insistence on telling the story.

Patel, Raj. A History of The World in Seven Cheap Things. Patel has produced various books on the devastation of capitalism and the food system. This one, as the title suggests, runs a through line between European feudalism and labor strikes today. Stuffed and Starved was my introduction to his work and I recommend it as well as an introduction to the global impacts of the “Western” diet.

I won’t get into it too much here, but Google the Jones Act to learn more. Basically, we are a colony and we don’t get a say over how anything comes or goes from our ports. It dramatically drains our economy to prop up the U.S. shipping industry.

See footnote 15. During World War II, according to the elders, food and supply shipments stopped coming to Puerto Rico for years. Because of a forced dependency, this undoubtedly meant a disaster for Puerto Ricans. The first mass exodus of Puerto Ricans to the states came immediately after WWII.

Level lines, perpendicular to water flow, which we will develop into terraces to slow water flow for better absorption and retention. While we basically live in a rain forest, the droughts between rainy periods can be devastating due to the poor water retention of degraded soils. Contour lines are identified by using a simple A-frame tool.

Plowing is very common, and folks with more money can afford to irrigate between droughts. Both are destructive and can dramatically damage the land.

Our farm is incredibly hilly, with very little flat area. So we look for the ridges and valleys to know where to plant. Water collects in valleys and brings sediment. The base of hills can also be a rich collection of soil. Ridges are usually the most eroded and have the least protection from wind. Our land is north facing, also creating large differences in how much sunlight a spot gets.

Beyond erosion, the soil ecosystem is always in flux, constantly being moved. Ants account for the most soil movement on earth. In making a single pile of compost and leaving it to decompose, some of it will inevitably be spread about by weather, insects, and gravity.

Yes, we have no running water, indoor plumbing, or electricity. It’s a miracle that you are reading this, typed on my notes app from the tent we live in. It’s a long story which we will get much more in to.

Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Go read this book. It’s so important in properly contextualizing the realities of ongoing colonialism. The author doesn’t rely on metaphors or ideas, just grounded facts. Alex introduced me to this book and she uses it in her class.

Lindqvist, Sven. Exterminate All The Brutes. Simply one of the most powerful books I’ve read, maybe one of the most important fictional books that the world needs to be able to grapple with reality. Raoul Peck’s films are based on this book.

Patel, Raj. A History of The World in Seven Cheap Things.

Imagine claiming land as yours property because you want the poop. Now no one else can use this land, because you want the poop. This is why we are fucked. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2014/07/08/by-kevin-underhill-the-guano-islands-act/

Peck, Raoul. Exterminate All The Brutes. A four-part film that intertwines the history of the colonization of Africa with the colonization the rest of the world, and the genocides that have been apart of each process.

Patel, Raj. A History of The World in Seven Cheap Things.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Undeveloped Africa. An important part of Panafrican canon, which details the myriad of ways that Europe’s actions for hundreds of years in Africa have produced the many issues that seem to baffle European policy makers today. Walter leaves no room for excuses and he was killed as a young man for his truth telling.

See footnote 31. The company is proud of the power that it could wield on the world.

The massacre of banana workers” in Spanish, but in English it’s known simply as the “Banana Massacre,” disguising the humanity of the victims.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/afghanistan-famine-threatens-millions_n_630db379e4b07744a2f9b8b1