Touring Through Vanishing Fields of Coffee

Agritourism is a symptom of disaster capitalism and it threatens life and land in the mountains of Puerto Rico.

“The issues with tourism boil down to how it changes the relationship between people and their land.” - A Puerto Rican graduate student I interviewed for this piece who chose to remain anonymous.

Our knee-high rubber boots knock loose chunks of asphalt that tumble downhill behind us as morning birds sing through the valley. The whole world is dark and pink except for the thin brilliant line that just breached the tree tops to the east, illuminating our walk up to Hiram’s house. We are super late. Hiram had to go into town for groceries so he left buckets for us by the radio he leaves on for the dogs- used five gallon paint buckets fitted with seatbelt straps. The radio is turned to a salsa station but as we grab our things and head down to the farm, the host is dramatically advertising solar panels to prepare for hurricane season. We zigzag down steep walkways, catching ourselves without ever breaking stride because around here slipping is apart of walking and falling is not a good option. We pass avocado trees older than we are on our way to start at the bottom of the coffee fields. We throw the buckets around our necks and press our bodies up to the first coffee trees. They’re only a foot taller than we are and they’re covered in red and green coffee berries, morning dew, fire ants, and occasionally wasps. Today’s assignment: grab everything that is not solid green. Certainly Hiram would prefer to sell only the fully ripe, plump, dark red berries for a higher price but he doesn’t have enough trees for that and he’s had a hard time just getting folks to pick what is planted. So he told us to harvest anything and everything usable.

As soon as we get going my mind begins to wander. This land has belonged to his family longer than the islands have belonged to the U.S. and not long ago coffee used to cover the entire face of the mountain, thousands of little trees all the way down to the river and dozens of people to care for those trees. All the neighbors remember it. Along this steep drop, any plateau could mark where a wooden house once stood, before the storms, vines, and termites did their work. I look for archeological clues in the surrounding forest. Straight lines of decorative crotons betray the illusion of untouched jungle and continue to stake the claim for families long gone. If coffee is such a cash crop, as $7 lattes and huge coffee franchises make it seem, where did everyone go?

Coffee picking is safer than cutting cane or climbing orange trees, but it’s incredibly monotonous work. When you get it just right, you can reach your hand to the trunk, pinch the branch and pull, knocking off berries like leaves off of a sprig of thyme, and ideally, they all land in the bucket hanging around your neck. Most attempts, however, are much less graceful, carefully picking the yellow-green from the green-green and accidentally pulling the hard unripe ones anyways, dropping the best ones, and sometimes breaking the entire branch and then quickly glancing around to see who saw. Some days I’ve counted the berries as I picked. A 28 pound sack holds 7,000. The first thousand takes 20 minutes, the second takes 30.

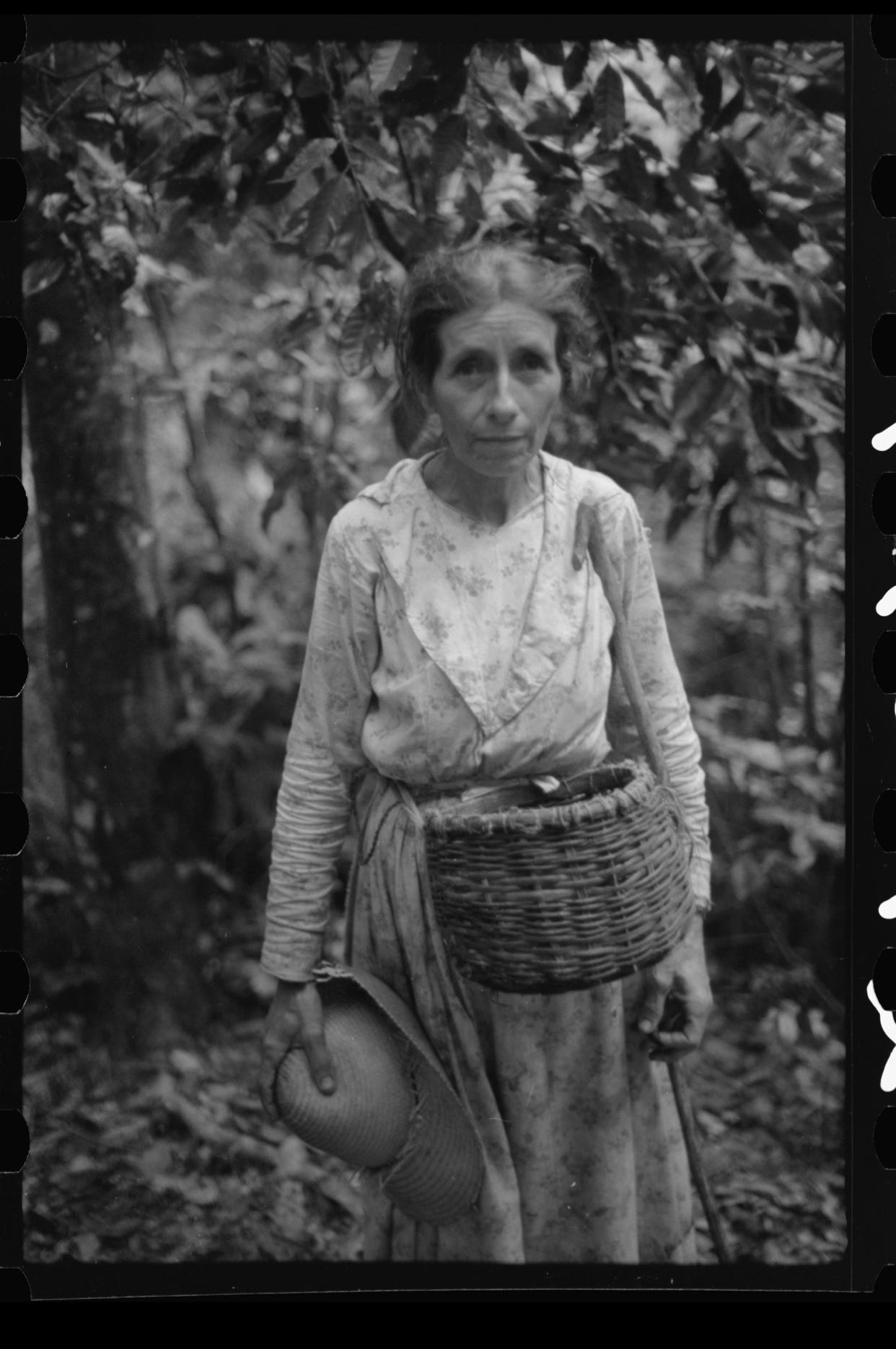

Within the same program that showed the world the faces of midwestern farmers devastated by the Dust Bowl, the Farm Security Administration documented rural life in Puerto Rico as well. This is how white America was introduced to us in the 1940s, as unnamed subjects standing in sugar fields, hanging tobacco leaves, raking sea salt, and picking coffee. I think of the woman in Corozal,1 another small mountain town some 30 miles east. I imagine her dress is homemade. Her right hand presses a straw hat to her leg, her hair still standing from having just taken it off. Her left arm braces a garabato almost hidden against her body. For workers pulling down tens of thousands of berries a day, the tool becomes an extra limb. Tied to her waist is a woven basket that she will fill and refill all morning. She is still, but obviously made tense by the camera-carrying, English-speaking Ukrainian man who just stopped her as he toured through the island.

That tension with tourism continues to exist. With the collapse of the agriculture sector comes uncultivated land. The forests that reclaim the land are gorgeous and full of natural wonders, sites that tourists love. Now, landowners in the mountains are being encouraged to move their attention to tourism, an option to diversify their income away from the dead-end industry of putting food on the plates of fellow Puerto Ricans.

Jack Delano’s FSA trip was the very best case scenario for tourism, where a foreigner did a lap around the island and photographed our struggles with the intention and access to help bring change. Most cases leave us feeling invisible, exploited, fetishized, and trashed. In this very best case scenario we still do not even learn the name of the woman in Corozal, much less her lived experience harvesting coffee for pennies, though her image lives on in the Library of Congress. Delano, born Jacob Ovcharov, added Puerto Rico to his Virgin Islands itinerary at the last minute. A few years later he moved to Puerto Rico permanently.

THREE THOUSAND. By now it is 8 o’clock, the air is getting thick and hot, and every thousand berries takes a full hour.

The 1940’s, the decade of Delano’s first visit, were especially turbulent. The independence movement reached its highest point since the U.S. took over. The U.S. involvement in World War II caused a complete shipping stoppage in Puerto Rico that lasted more than a full year, causing shortages of every kind. It was also the decade of land grabs which led to the decades of tourism that followed. Poor people in the mountains were moved to the cities to work in factories, hospitality, and service industries. The first mass waves of Puerto Ricans moved to New York on the back of the USS Marine Tiger. I look down the mountain at Alex, her neck weighed down by a nearly full bucket, and I feel that in 80 years not much has changed.

Farmers in the mountains of Puerto Rico, like people in poor countries everywhere, have been coerced into planting coffee for centuries. Decade after decade, as more acres of forests are turned to coffee plantations globally, the price of coffee drops, and because the colonized nations of the world were designed and developed to produce just a few crops for export, they became dependent on the price and, counterintuitively, become even more dependent as it drops. At this point, a single disaster could destroy everything, and ours was named Maria.

For investors, Maria created opportunities. It provided the perfect clean slate, like Hurricane Katrina did to New Orlean’s Lower Ninth Ward, for them to recreate it how they saw fit. The economies that have developed around preparing for and responding to disasters, wars, pandemics, and financial crises make up disaster capitalism. At the center of disaster capitalism is what investigative reporter and author Naomi Klein’s calls the Shock Doctrine. Klein started researching capitalism‘s dependence on the power of shock during the early days of the occupation of Iraq.

“After reporting from Baghdad on Washington's failed attempts to follow Shock and Awe with shock therapy, I traveled to Sri Lanka, several months after the devastating 2004 tsunami, and witnessed another version of the same maneuver: foreign investors and international lenders had teamed up to use the atmosphere of panic to hand the entire beautiful coastline over to entrepreneurs who quickly built large resorts, blocking hundreds of thousands of fishing people from rebuilding their villages near the water. "In a cruel twist of fate, nature has presented Sri Lanka with a unique opportunity, and out of this great tragedy will come a world class tourism destination," the Sri Lankan government announced.”2

Klein compares shocks, such as the devastation witnessed during and since Hurricane Maria, to the psychological experience of torture. The CIA’s information gathering technique of “coercive interrogation”, she explains, utilizes extreme sensory experiences to confuse reality, making people unable to recognize themselves, ultimately softening them up to make them more suggestible.3

“That is how the shock doctrine works: the original disaster—the coup, the terrorist attack, the market meltdown, the war, the tsunami, the hurricane — puts the entire population into a state of collective shock. The falling bombs, the bursts of terror, the pounding winds serve to soften up whole societies much as the blaring music and blows in the torture cells soften up prisoners. Like the terrorized prisoner who gives up the names of comrades and renounces his faith, shocked societies often give up things they would otherwise fiercely protect.”4

FOUR THOUSAND. I grab a guava off the tree and take break that’s too short. The radio is playing Ismael Rivera’s “Lejos de ti”.

The unofficial history of this land is that it has served as the commons, keeping people alive when coffee prices drop. Our neighbor Salvador foraged and sold wild yams to make ends meet. From the lake at the bottom of our parcel small boats load up bananas along the bank. Cars pull over and old men fill bags with mangos, oranges, and avocados that collect in the gutter. Elderly women forage wood and grass for cooking. Families use the river for fishing and swimming. Everyone retells childhood adventures making chocolate from our massive cacao tree.5

For wealthy tourists to feel safe around poor locals, fences go up, privatizing and enclosing the commons. This is happening with coastal hotels and condos that illegally privatize public beaches, with eco-lodges that build cheap gazebos right in the middle rivers, and with airbnbs that fence in the waterfalls so that people from the neighborhood can no longer seek refuge from the heat. As farms in the mountains become tourist resorts, the people lose out on more resources that have kept them alive.

Hiram is a community leader. He’s the guy that everyone knows because he comes from a huge family and because he is constantly helping folks, organizing community clean ups, delivering free food, and connecting people to solve problems. We are lucky to have him as our closest neighbor. One of the ways we show our gratitude is by picking his fields when he’s in need.

Hiram sincerely thought he was doing us a favor when he signed us up for a visit by representatives of two universities from the states and two agriculture agencies, all working together to increase agritourism in the mountains of Puerto Rico. Their project focuses on farm tours, Airbnb stays, glamping, anything to get people with money to visit the mountains and spend that money. The group got a massive grant to jumpstart the process. For us, the visit was awful. The last thing an entitled American professor of tourism wants to see in their big project is people living under a tarp. Of the five visitors, only two were Puerto Rican, and both were graduate students with little power in the dynamic. Alex and I could tell that they, too, were mad about the project. Nydia, which is not her real name, agreed to be interviewed about her experience, but asked to remain anonymous for fear of losing her position. Details in the interview have been changed to maintain anonymity.

Nydia has been working on the project for three years, but mostly behind the scenes, and she believed that the $300,000 grant was being used to help farmers in need. So when she finally got to join the trip and see what was really going on, she said that it was “disappointing to see so much suffering despite all that money being funneled through.”