Waiting for Muchachos

Living in Puerto Rico in the midst of a health system collapse.

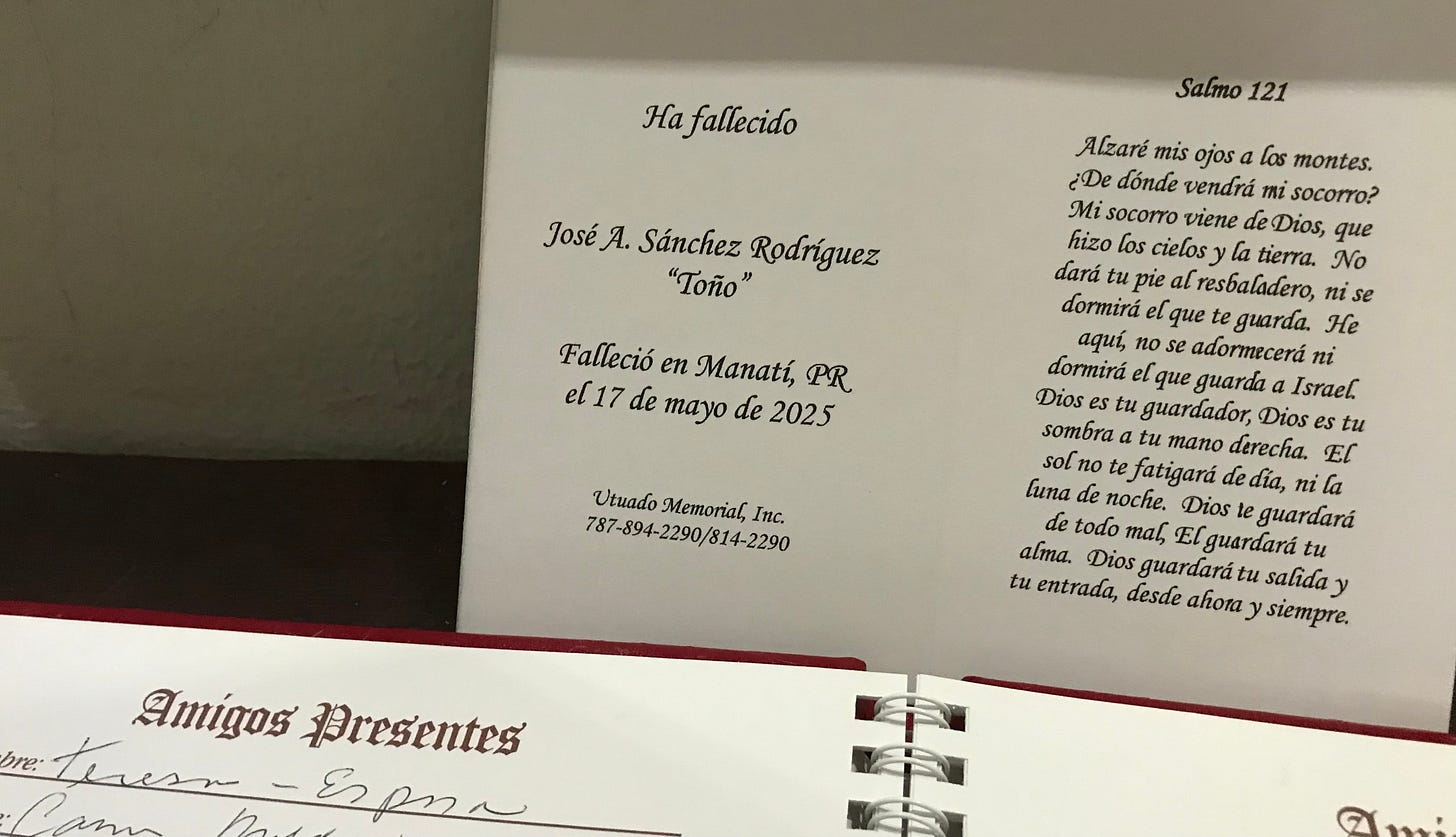

Author’s note: Toño died the second week of May and I wrote much of this immediately after. Although it took a few weeks to compile the relevant data, the original references to days and times remain.

“¡Muchachos!” Toño yelled each evening as he got home from work. Running up the driveway, jumping off the breadfruit tree, and climbing down from the roof, gray, black, and yellow cats would come running from every direction. Toño cared for nearly a hundred animals, many stray and many who he and his wife Teresa adopted over their 25 years of marriage. No matter how long his day had been doing seasonal farm work or day labor on wealthy estates, he made sure that they all ate before he did.

Toño died suddenly last night, shocking the neighborhood. We await the autopsy results to determine the cause of death, but we all know why he died, because he lived in Don Alonso. Toño hadn’t felt well that evening and Teresa suggested going to the hospital, but Toño shuddered at the thought of spending all night in a waiting room only to get a few minutes with of an overworked, under-resourced doctor and to come home with a bill he couldn’t afford to pay. He tried sleeping it off, unsuccessfully. It was the middle of the night when he told Teresa he wanted to go to the hospital. Teresa called her brother Hiram to drive, who sprung out of bed and got on the road immediately.

Highway 140 is a mountain road with sharp turns that ride the edges of plunging cliffs. Cement barricades mark sections of road that have collapsed from our many notorious landslides. It’s about a 25 minute drive from Don Alonso into Utuado pueblo, which has long been the hub of the mountains, hosting for all the surrounding towns a courthouse, national guard and state police stations, and the only emergency room in the region.

Last night Hiram didn’t take 140 into Utuado like he normally would because to start off the year Utuado’s hospital, Metropolitano de la Montaña, shuttered its emergency room department and then, to avert the closure of the entire facility, transitioned all its services to exclusively mental health.1 The executive director, Janice Cruz Pérez, assured the community that despite the loss of services for the impoverished, isolated, and elderly population of the mountains, the hospital will still work to bring “emotional stability and hope to the vulnerable population.”2

Hiram cut through the backside of the neighborhood and took Highway 146 towards Ciales. Since the closure of Metropolitano de la Montaña, the nearest 24-hour emergency room in is Manati, over an hour’s drive without traffic. Fortunately, it was a clear and still night, making the best conditions for the drive. Had there been wind or rain the group would’ve likely contended with power outages, fallen trees, and flooded bridges. Our region is known internationally for its unique isolation and inaccessibility during and after storms.3

As the jeep full of 70-somethings winded through the valleys, dodging potholes and wildlife, there was a breath of relief as they got to Ciales. The roads get progressively wider and straighter and streetlights become more common. It was the coldest part of the night. Toño, exhausted, covered himself in a blanket and laid down in the backseat. Hiram picked up the pace as they neared Manati. “I looked away for a minute and then when I checked on him again he had stopped responding,” Teresa told us. Hiram said they were just blocks away from the hospital. When they arrived, Toño had no vitals. He was pronounced dead moments later.

Our neighbor Toño died this morning in the back of his brother-in-law’s jeep.

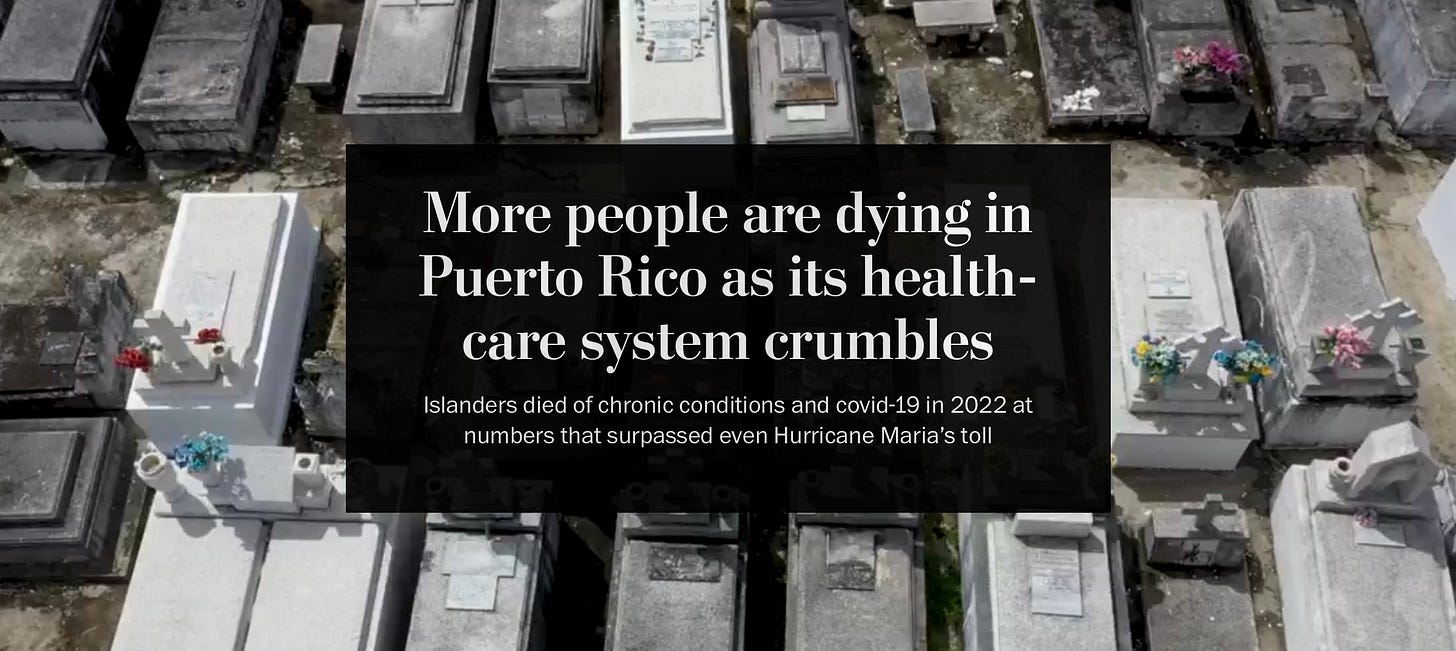

Puerto Rico’s healthcare system was “headed for an all-out crisis” back in 2015.4 It was “collapsing” in 2016.5 In 2017 the Health Resources and Services Administration deemed 72 of Puerto Rico’s 78 municipalities as medically underserved areas.6 Then Maria, the earthquakes, and COVID, all while the junta takes away our public funds and the exodus takes away our medical professionals. At this point medical services barely exist, with massive staffing shortages, crippling debt, and continued closures making access difficult or outright impossible. 8 of 10 hospitals operate at a deficit.7 People wait months to see specialists—the few willing to deal with Medicaid’s (mal)practice of under reimbursing our physicians.8 Patients leave with incredible debt and misdiagnoses. And the most unfortunate scramble for hours seeking emergency medical care, or die at home waiting hours for the ambulance.

After Puerto Rico successfully struggled for self determination in the 1950s—albeit undermined from the start— the public health system that was established was ahead of its time and produced drastic improvements in health outcomes. “That system managed to virtually eradicate the parasitic conditions that plagued us at the beginning of the century, when we only had a life expectancy of 32 years, one of the lowest in the Americas,” Ibrahim Pérez, a gastroenterologist, professor, and researcher told BBC Mundo. “It led us to a life expectancy of 72 years by 1970, number 14 in the world at the time.”9

The collapse began in the 90’s with the fierce privatizations of the first Rosello era. ”Decades later, after years of budget deficits and complaints about services, the system underwent a drastic change starting in 1993 when Governor Pedro Rosselló González – father of ousted Governor Rosselló Nevares – introduced a new model, baptized as the Health Reform, the same as the failed initiative by President Bill Clinton. With it, Rosselló González sold most of the public health facilities, replacing government services with contracts with private health insurance companies,” reported the Center of Investigative Journalism (CPI for its initials in Spanish).10

Our neighbor Toño died this morning in the back of his brother-in-law’s jeep because he lived in Don Alonso. Now we’re sitting with Teresa at home, which is full of people, the sobs of strong women echoing off the walls. The stream of visitors doesn’t slow until the sun starts to set. Everybody has a story of someone who they’d also lost too soon, too suddenly.

This is not another warning before the crisis hits. The storm that’s been barreling towards us for decades has arrived with full force and is sitting on top of us, reaping havoc. Every day access gets harder and health outcomes get worse. Despite our population dropping to its lowest in 45 years—due in no small part to the health crisis—more people died in 2022 than in 20 years prior. “Specifically, that year there were 35,400 deaths, 3,300 higher than expected.” Omaya Sosa Pascual, journalist and editor at CPI, told BBC Mundo.

Since then the government has made the data harder to access and local orgs have been forced to rely on FOIA requests to know just how many people are dying. Sosa Pascual said the trend continued in 2023, but because Puerto Rican authorities have blocked part of the data they have been unable to conduct further investigations. The Department of Health promised to produce a report on excess deaths, which would be published in 2024, but that never happened. All we have are the visceral reminders that in the face of the crisis, they do nothing, and now Toño is gone.

Our neighbor Toño died this morning in the back of his brother-in-law’s jeep because he lives in Don Alonso, where it has been decided that old people need no healthcare.

If only Cuba could send us doctors. Our biggest neighbor has more than 24,000 doctors working in 56 countries worldwide, more medical personnel dispatched to poor countries than all the G8 countries combined.11 The doctors set up for years in remote, impoverished areas around the global south, saving countless lives by being where other doctors aren’t. Most of the Caribbean benefits from Cuba’s world-renowned medical programs but Puerto Rico and Cuba are twin victims of the US blockade.

Alongside their permanent medical outposts, Cuban doctors also dispatch to disaster zones. It was not long ago that the Henry Reeve brigade marched into the streets of Italy, at the height of COVID lockdown, to international applause. The group’s name came after Katrina ravaged New Orleans. Cuba offered to immediately dispatch more than 1500 medical doctors with 37 tons of medical supplies, having coordinated with Florida-based Gulfstream Airways to fly them into the affected area free of charge.12 Washington did not respond.13 Cuba then doubled down on its internationalist efforts, dubbing the volunteer medical program the 'Henry Reeve' International Contingent of Specialized Physicians in Disaster Situations and Serious Epidemic. Reeve was an American soldier who helped Cuba fight for independence.

Every president since Bush Jr. has tried to take doctors away from poor Caribbean countries so as to further isolate Cuba, calling their medical internationalism human trafficking.14 Trump recently escalated further, threatening Caribbean leaders directly with visa revocation if they continued to work with Cuban doctors,15 to which said leaders resoundingly denounced, insisting that they’d rather lose their visas than to have poor and working people die.1617

When Cuban doctors prepped personnel to send to Puerto Rico after Maria, during the most critical weeks of the crisis, Washington again ignored the offer. The country pledged to send a field hospital, 39 doctors, and four brigades of electric workers that could’ve dramatically altered the outcomes of the disaster.1819 Instead, the American doctors that flew in from the states struggled to navigate the island’s roads after the storm; the New York Times wrote about one New York doctor who gave up and turned around after struggling to reach Don Alonso.20 Sovereignty, the right of a people to make their own decisions, to design their nation in the ways they see fit, is yearned for most deeply inside the colony’s weary heart, precisely where it feels farthest away.

Our neighbor Toño died this morning in the back of his brother-in-law’s jeep because he lived in Don Alonso, where it has been decided that old people need no healthcare because its another forgotten hub of a dying industry, on a colony out in the ocean.

Giving was Toño’s thing, and he’s given us so much over the years. He taught us a lot about what it means to be apart of this community and he left big shoes to fill. We tell Teresa not to worry; between us and the rest of the neighbors, she will be taken care of.

We’re reminded of Celeste Bremby’s teaching of the parable of the choir. “A choir can sing an impossibly long note because individual singers can drop out to breathe as necessary and the note goes on.” Bremby saw this as a useful lesson in how to work together towards long term goals of mutual support. “Communities working toward social justice must function like the choir. You take turns holding the note, while others rest.”21 We decide we’ll take up the daily call of “muchachos!”, so that now Toño may rest.

https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/the-puerto-rican-healthcare-crisis-10-things-to-know/

https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/the-puerto-rican-healthcare-crisis-10-things-to-know/

Robert Huish and John M. Kirk (2007), "Cuban Medical Internationalism and the Development of the Latin American School of Medicine", Latin American Perspectives, 34; 77)

Celeste Bremby, a Black musician and retired staff at the University of Northern Iowa is credited with this quote, but the internet has been largely scrubbed of her name, including the original press release from her university, perhaps due to anti-DEI threats. Instead, popular memes about the parable of the choir credit “a friend” who “once told me” instead. She deserves credit.