Yellow In Spite of Myself

The Carlisle Indian School and Puerto Rico.

Querido Boricua,

America has never known what to do with Puerto Ricans. From the very beginning there was panic: they came for the land and resources, but how will the tens of millions of people (from here, Cuba, and the Philippines) abruptly put under U.S. control fit into the complicated American nexus of race and rights? Assimilation was never as nonviolent as we have been told.

The Apology

A few weeks ago, in a last ditch effort to solicite native votes in key swing states, President Biden went to Arizona to apologize for the residential school era, the century and a half of kidnapping, forced assimilation, torture, and death—lots of death—suffered by generations of indigenous youth inside “Indian Schools”. The apology—proven sincere by our elderly president mustering the energy to yell out, “I formally apologize!” “I formally apologize!”—is historic. It’s the first time they’ve even acknowledged the horrors, though it left people asking for action: land back, the release of Lenard Peltier (himself a survivor of the residential schools), and a federal truth commission to release records of the many church-run boarding schools still hidden from scrutiny.

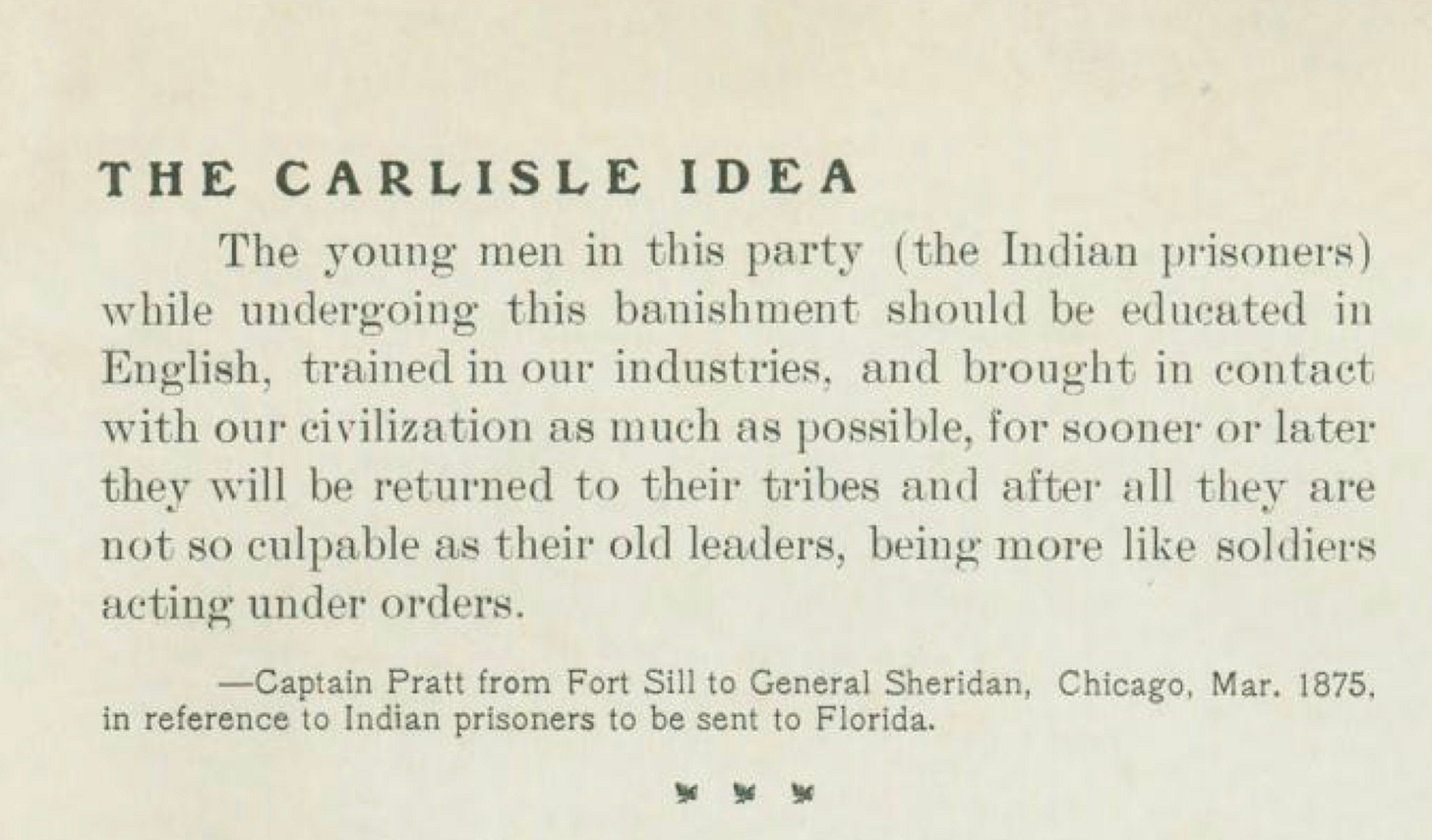

The goal of the Indian School was to eliminate inside of school houses what could never be eliminated through wanton state terror: troublesome Indians. After Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission uncovered for the world graveyard after graveyard on residential school grounds, non-Indigenous America started learning about their own recent histories. Most brutal in its methodology of “kill the Indian, save the man” was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, isolated far away from reservations (read: concentration camps) as a tool of the assimilation process. During its time, the Carlisle School was recognized globally as a cutting-edge assimilation program and the school existed through decades of federal funding. Visitors came from Europe, Asia, and Latin America to watch and learn. A visitor from the Indian Department of Hampton Institute (today Hampton University) wrote of how impressed he was by the Carlisle student performances in arts and skilled labor, yet lamented that Uncle Sam was wasting money on the forks that were yet still beyond the reach of Indian civilization strategies. Native students, meanwhile, were choosing suicide rather than life at Carlisle. “Carlisle students were working in the factories of Ford, General Electric and Bethlehem Iron and Steel. Girls were getting pregnant. There were prostitutes and bootleggers in town supplying the school's needs. Some students were at Carlisle for twenty years, some stayed only a month. Of all the students who attended Carlisle only 600 graduated”.1 Upon arrival, students were forbidden to use their original names, languages, clothes, hair, or customs—the uncivilized attributes that needed to be eliminated. Early Carlisle practices included before and after photos of students, photographic proof of the Indian becoming civilized. The first child that was buried at Carlisle was a student there for only four months, a 16 year old Cheyenne youth who had been renamed Abraham Lincoln.

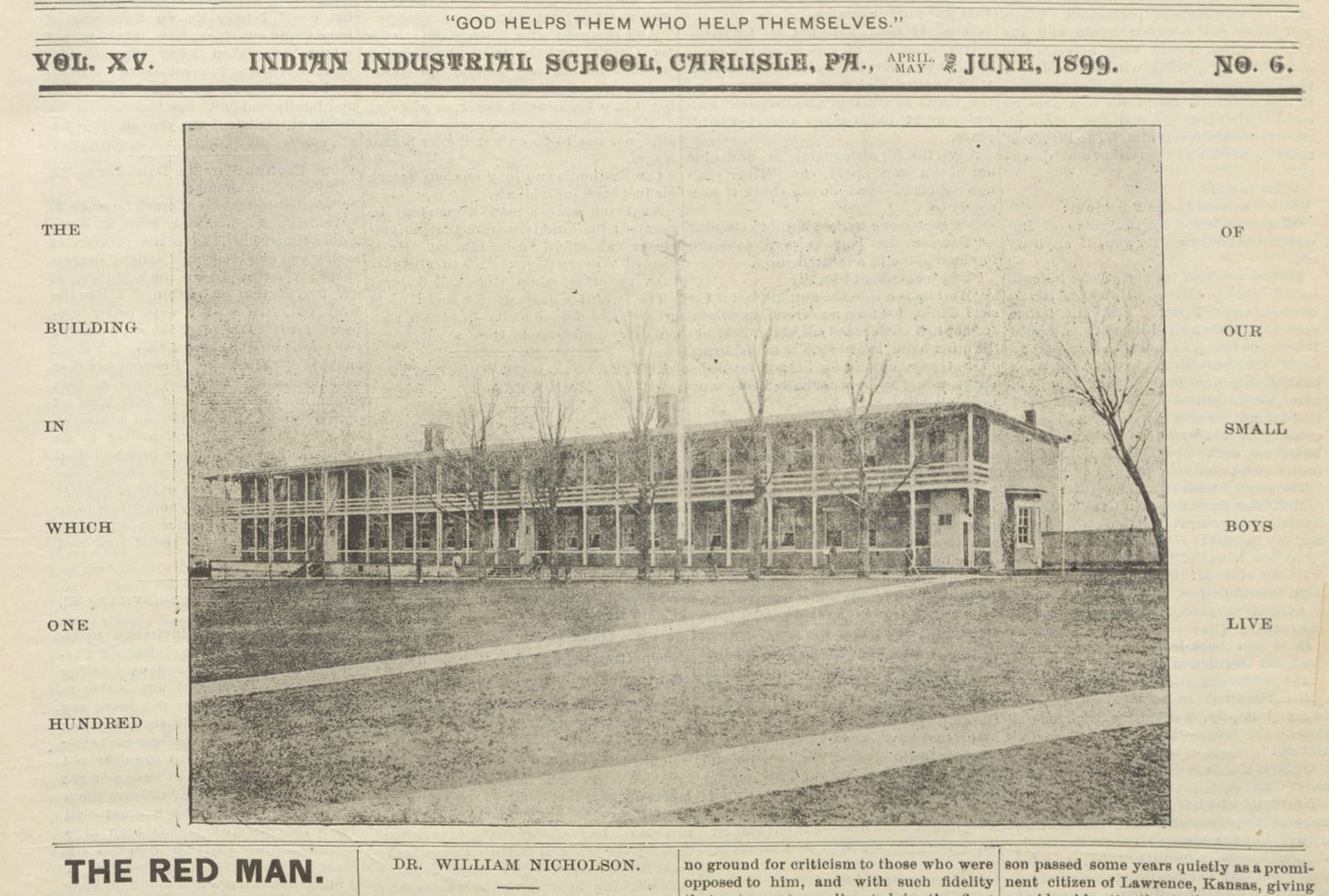

It was assimilation disguised as education and the first “pupils” were “prisoners of war,” code for youth that were found “trespassing” on their homelands, outside of the bounds of the reservation without permission. It’s said this group of Apache youth were protecting the last herd of buffalo when they were scooped up by an Army Lieutenant Richard Pratt and imprisoned for two years before he decided to use the prisoners for an experiment. He would use civilization as a weapon against delinquency, making them more amendable captives, part of a longterm goal to dismantle reservations and claim the remaining land. The Carlisle School drew inspiration from the already treacherous Indian Department at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) with one key difference: isolation, far away from reservations, in a native-only institution. Tens of thousands of native youth went through Carlisle, a novel experiment in making enemies of the state into servants, industrial workers, and soldiers2. The school sent reports on their work out to the nation in a weekly paper which also served at Lt. Pratt’s personal manifesto, The Red Man and Helper. It was a periodical for the progressive white leftist that wished to conquer lands with a softer touch, forcing native people into servitude rather than carrying out more massacres, in what was known as the “Friend of the Indian Movement” and Lt. Pratt was a movement leader. The moment his Indian school idea was approved he went immediately to the Dakotas and the Southwest to gather pupils he could rescue from “the blanket” by bringing them far away into the cradle of whiteness. Carlisles’ proudest tool of assimilation was even further isolation in “the outing system”, a form of human trafficking3 where children served as live-in workers, caretakers, and maids for white Christian farmers and families, friends of the school. Maybe here they could learn to use a fork. Although Carlisle was forced to close in 1918, such residential schools existed into the 1970s and the trauma, understandably, still reverberates.

I want to remind you of something you may never have been told.

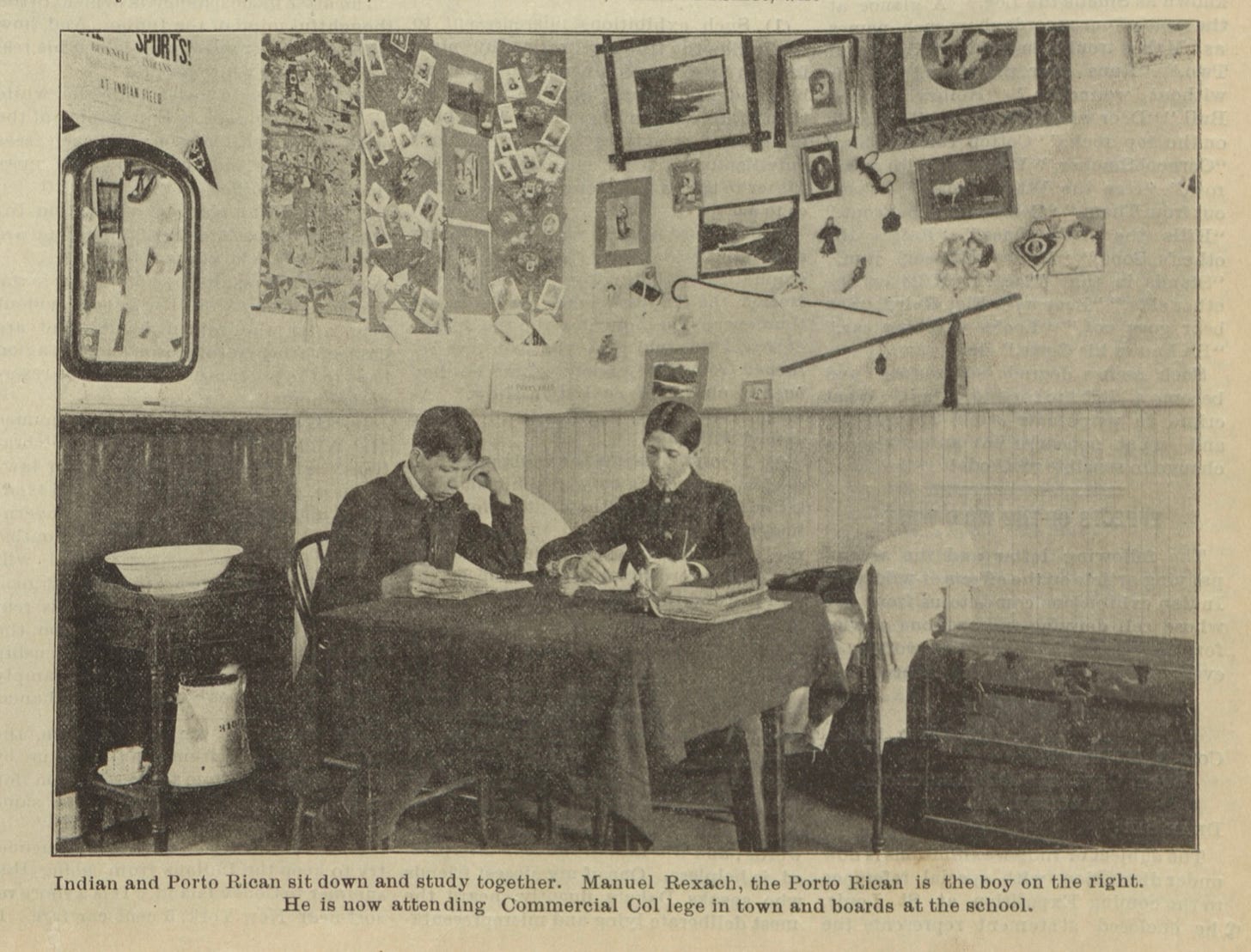

Puerto Ricans were sent to Carlisle too.

The first Puerto Rican kid that was taken to Carlisle, Juan Santana, was brought there by soldiers a month before the war was over, a war crime by today’s standards. It’s important to remember that Puerto Ricans were brought into the US at the nadir of race relations, when reactionary white terror was its harshest and most public. As the warship crawled up the east coast towards freedom and democracy, unbeknownst to Juan, it passed the southern port of Wilmington, where on Election Day just a week earlier, white supremacists carried out a massacre and coup d’état to take control of the majority Black city. Two Wilmington regiments that had served in the invasion requested to leave Puerto Rico early so they could take part in the insurrection and racial terror that would usher in Jim Crow in North Carolina and rid the state of a single black representative for almost a century.4 Juan didn’t return home for nearly six years.5

The assimilation tactics were the same ones used on the rez: go for the children of the leaders, isolate them, replace their identity with one easier to conquer, and send them home to disrupt the nation. In an interesting twist, this meant that the Puerto Rican kids sent to Carlisle were the relatively rich, or they had been, before America debuted its policy that would instantly devalue the peso by 40%.6 These kids were sent on scholarship and were some of the last students sent home when Carlisle finally closed. Some students ended up staying in Pennsylvania, constituting some of the earliest migration to one of the largest diaspora communities.

1901

Barely two years after Juan arrived, the initial trickle of Puerto Ricans students had become a full flow of students systematically shipped far from home. The Carlisle archive shows a student body made up of kids from 77 different federally-recognized indigenous nations with Porto Rican listed between Ponca and Potawatomi. That year there were 43 Puerto Ricans, making up the 6th largest constituency, surpassed only by Seneca (149), Oneida (109), Sioux (90), Chippewa (80), and Cherokee (62), and the colonial government, freshly installed, was eager to send hundreds more.7

But we were problem pupils.

We kept speaking Spanish. 1 in 12 students ran away. 1 in 5 were returned home by their parent’s orders. Only 7 ever graduated.8 The experience was so bad that the government eventually reversed its initial decision, insisting that we were not, in fact, Indian enough to attend the Carlisle school, which would be a convenient closure to Puerto Rico’s Indian school era. Yet such a simple conclusion alludes us.

The federal government decided that with how many Puerto Ricans they wanted to assimilate, the money being used in sending students all the way to Carlisle, Pennsylvania— the first five dozen costing more than half a million dollars in today’s money9—might be better spent setting up industrial schools directly in the archipelago. Many industrial schools were built, training generations for low paid industrial work, and the line between schools and prisons has been blurry ever since. The old juvenile detention center photographed in Dont Get Locked Up In Puerto Rico was an industrial school, as is the only women’s prison today.

The US decided they would face less opposition in the school system overhaul if they kept as many existing teachers as possible, though they required teachers learn and teach in English, and they hired Americans to come staff director positions and lead educational boards. The first appointed governors, military men, solicited help from the Pennsylvania school started by their Army friend, “the Indian Helper”.10

The Porto Rican and Helper

Ruth Shaffner came first; she was the scholar. For eight years she’d been in charge of the girls at Carlisle and served as field agent, tasked with recruiting new students and following up after they’d returned home, to study if the assimilation stuck.11 She gave lectures and wrote papers on contemporary strategies of Americanizing the different races and her work was considered required reading for elite literary, academic, science, and political circles. While in Puerto Rico she served as president of the World Women’s Christian Temperance Movement, a holistic evangelizing-Americanizing apparatus which included education and industrialization, and was rapidly establishing missions from Cuba to China. When Spain signed over Puerto Rico and Ruth’s fiancé unexpectedly landed a job at the new Ponce Improvement Company (taking advantage of the boom industry around rapid Americanization) the couple left for New York immediately, marrying along the way in Philadelphia, and caught the first ship down to America’s new curious “West Indian” possession.12 Within a year Ruth was the Ponce district superintendent, in charge of 1,000 employees, 46 school houses, and 50,000 students.13

Jennie Ericson followed Ruth’s lead, seeing the opportunity to continue spreading the gospel of Sloyd, the Finnish-style education that blends woodworking with Christian values. She found work immediately at the brand new San Juan Normal School since, like Carlisle, the goal was to rid students of their family’s language, so her limited English and nonexistent Spanish were of no issue. Jennie was pleased to be in Puerto Rico, as she’d come to America to escape the Finnish famine, but her consistent complaint regarded the need to be even more severe with punishing Porto Ricans than she had with Indians at Carlisle.14

When the Normal School burned down15 classes were relocated for years to the Benefencia Asylum. The school occupied one half of the building—the old orphanage—and shared the other half with the insane asylum.16 In the summers Ruth brought Jennie down to Ponce to help start wood working departments in the industrial schools17 and to this day European woodworking tools are sold at local school supplies stores across Puerto Rico.

Carrie Weekley came down as soon as Ruth took charge, and she brought her sister to come teach with her, illustrating the reach of the Carlisle sphere. When their boat arrived in Ponce, she later confessed, she nearly was unable to disembark because she was too afraid of the Afro Puerto Ricans working the docks. Ruth sent her husband to rescue the pair and bring them in.18

Though there was no formal segregation policies installed in Puerto Rico public schools, it is not difficult to imagine how this group of white women, transferring from an Indian Boarding School during the height of anti-Black terror and indigenous genocide, set up the first American schools and policies in Puerto Rico, starting in the historically Black city of Ponce. With these teachers and administrators put in charge, the abusive assimilation normalized at Carlisle was undoubtedly transferred into the earliest days of our Americanized public school system.

Ruth, the scholar, was a powerhouse for Carlisle. When Lt. Pratt needed theory to prove the need for and benefits of the Carlisle School’s special methodologies of isolation, he called on Ruth to write something up for the academy. In “Civilizing the American Indian”, she wrote: “As the years pass and we come to know the Indian as an individual, we are convinced that what has so long been recognized as the Indian problem has never had a just cause for existing at all. The Indian massed in tribes is the problem. The Indian with individual opportunity away from the tribe is no problem.”19

Ruth was in her early thirties when she arrived and saw before her a long life in the field of civilizing, but God cut her missionary vision short before it started. Just three months after the newlyweds had arrived, Puerto Rico was slammed by the apocalyptic San Ciriaco hurricane, devastating the island like never before and drowning five hundred of her new Ponce neighbors. Ruth developed an illness during the aftermath that would end up taking her life. Though her tenure was short, Ruth made lasting impacts on the school system and she would continue contributing to the scholarship of civilizing ‘Porto Ricans’ though her health issues eventually precluded her from reentering the classroom.

Dedicated to the cause of civilizing, the last thing that Ruth did while in Puerto Rico was to round up as many children as possible to bring with her back to Carlisle.20 She wanted to bring girls, who she believed were predisposed to enjoy servitude more than white girls, but she knew Puerto Rican parents were reluctant to give up their daughters. She eventually brought back with her five Puerto Ricans from families that had “lost their means through last year’s hurricane or in the transition of government,” including the first four Puerto Rican girls to attend Carlisle. Their names were Matilda Garnier, Zoraida Valdezate, Felicita Medina Americus, Adela Borelli, and Paul Seguí.21 After enrolling them in the school she signed the girls up for the outing system under her watch, bringing all four of her “Porto Rican girls” home as live-in servants for over a year, until she moved to California still in search of more treatment. Only one would ever graduate.

For years until her death she continued publishing articles. She opened “the Education Problem in Porto Rico”22 with:

“The people of Porto Rico cling to the idea of absolute self-governance and resent our assuming the scepter of power in any wise. They fancy themselves entirely capable of managing their own affairs in matters educational no less than political. They would have all American influence, in their schools as elsewhere, withdrawn.” Yet, in the paternalistic spirit of Americanization just as present then as it is now, Ruth spent the rest of the article explaining why, when it comes to responsibility of civilizing the Porto Rican, “the acquirements of a native teacher are very inferior”and suggested that the best way to assimilate Puerto Rico would be “to honey-comb the land with institutions like Carlisle and Hampton”.23

Yellow?

There’s a question on government forms, however simple, which gets me every time. Under race, the check box options are blanco, amarillo, or negro. Is it a question of pigment? If so, why did over 75% of Puerto Ricans select white since the 1940s? The white people I grew up around would (angrily) disagree, but race is a social-geographical construct. When the question is stripped of its reference to pigment, then we are left with the real question people are being asked: how civilized are you between these three colors? In the 2020 census, surprisingly, the amount of people who chose white dropped by 80% to just 17% total, which brings up a lot to consider about how Puerto Ricans perceive ourselves, especially as more and more people are rejecting the political and territorial status quo.

There was scant discussion of the race of Puerto Ricans brought to Carlisle, aside from occasional notes of students being “mostly negro;” we can easily imagine the repercussions suffered by these youth, experiencing Jim Crow, USA for the first time. Otherwise, America funneled us neatly into the category of Indian, of “Porto Rican” tribe, shaving off the vast complexities found in an archipelago that has always been at the center of international travel and trade and was one of the most densely populated places on earth, settled and shaped by people from all over the world. Next to tribe, many students penned I Am Not Indian, yet Americans continued to send kids, and Puerto Ricans were at Carlisle for 20 years, until the school’s forced closure.

On the day that 16-year-old Juan Jose Osuna arrived at Carlisle from Caguas, he fell in with the kids that were busy harvesting onions, kept orderly with a whip. Juan stayed at Carlisle for less than a year before exploiting the outing system to escape upstate. He stayed in the states for some years, trying to get the education Carlisle would never offer, and soon published his doctoral thesis at Columbia University, Education in Porto Rico, under the name John Joseph Osuna.24 When he finally returned to Puerto Rico, he reflected on his time at Carlisle in Indian In Spite of Myself, where he detailed the repercussions of being determined Indian by the US government. The work has been compared to Fanon’s The Fact of Blackness for naming the inherent violence in being categorized as a minority, and how the myth attached to the color designation has real world impacts.

Before the president’s apology started there was ritual, including young children dancing and elders keeping the rhythm with maracas. I see Latinidad—probably why the “Porto Rican” students at Carlisle fell in easily with the “Indian” students from the southwest. Not long into the speech, a woman interjected, “what about the children in Gaza?” and asked how the president could apologize for the genocide on her people while participating in another genocide against indigenous populations? (With helicopters named Apache, no less). It was a brief moment that held the potential for global solidarity, and it collapsed with the force of the entire crowd shutting this woman down. Above the inaudible commotion a man shouted, drawn out and in a country accent, “Geett ouuutttaaa hereeeeeee!” And she was escorted out. People seemed pleased that the president could continue, that the “Palestine Problem” would not become theirs to grapple with, as if there is no room for such solidarity.

The Puerto Rico problem has always been the same: what do we do with these people? The Insular Cases still shape our legal designation as second-class, though they were ruled while the first Puerto Rican students were being sent to Carlisle, when Indigenous extermination no longer required bullets and the U.S. populace was fire bombing Black towns and neighborhoods that saw too much success. Where do they belong on the complex American caste system? America still doesn’t know, and that fact remains a larger determinate of our continued colonial status and our peculiar kind of citizenship than any referendum offered to the people of Puerto Rico.

What box do I choose: white, yellow or black? No answer feels comfortable. I didn’t grow up coded as Black like my father, nor was I called yellow as a slur like my Filipino friends, but if America taught me anything it was that I was certainly not white and I’m not going to start now. I choose yellow in spite of myself.

Costume as academic rigor

During undergrad I had professor, Paul Thulin, who was proudly Swedish, and who made photography projects about his generational wealth and rightful claim to part of America as a descendant of early European immigrants, i.e. his whiteness. A scary individual, credibly accused by multiple female and non binary graduate students of abuse,25 he brought his own military boarding school trauma into our art classes. I did not learn until after the 2020 Movement for Black Lives that Paul is Puerto Rican, when he, in his middle age, while securely taking home a $100 thousand dollars salary, tacked on the end of his Swedish name his maternal surname, pretending that he’d in fact been born and raised in Puerto Rico, where using two last names is common.

He had started a photography project about indigeneity in Puerto Rico, as so many white Puerto Ricans do. A year after Maria passed, his wife confessed to me that he’d never have even considered visiting Puerto Rico to meet the people who share his maternal name if it were not for the new photobook project. Then he came here, to our little mountain town, in his words a “pilgrimage” searching for Indians through which he could view himself. He met a man in the park we pass on the way to my grandfather’s house or to scoop horse manure for the farm, and in exchange for taking his portrait, Paul bought reluctantly him lunch. Drenched in outdated racist tropes, he’d discovered a ‘real taíno’ for his California collectors and Italian donors.26

What is most striking, coming out of weeks of researched, immersed in the language of the post-industrial imperialist United States—the telegraphs between Indian School teachers, government reports on assimilation results, many academic articles about the Indian Problem, the Negro Problem, and Porto Rican Problem, and all of their roles in the post-slavery Servant Problem—is how similar Paul writes about our Utuado neighbor today. “I was told he was a real Taino, none of that bullshit wannabe dress up type, seeking USA grants, drumbeats, and sex in leather”. He was a “real Taino” who was all clay, sunshine, and herbs and had a talking dog who, erratic like his owner, flipped back and forth between idleness and extreme violence. The pilgrim was “scared, off grid and alone” and acknowledged “panic” and “fraud.” He paid for his “path to indigenous knowledge” with lunch. Safe now, he can reflect with the viewer how he’d passed “into the mystical universe of a hungry Taino.”

His project, Island of Palms, is as voyeuristic as would be a series about Lakota people titled “Land of Corn.” Worse yet, the reference is to the ubiquity of palm trees on the islands—which are as unique to Puerto Rico as grass is to South Dakota—and the obvious benefit of using palm as a building material when lumber or cement is too expensive. By using that name for his Indian hunt, Paul the Helper erroneously conflates poverty with indigeneity, the exact same accusation that, one century ago, got Puerto Rican kids sent to Carlisle.

What has happened here? Why does a Swedish academic get to pass off tired tropes of mystical Indians, applying his own judgments of Indianization, caring little for how the person identifies nor the context and ramifications of that identification inside Puerto Rico? Is it an unremarkable case of white supremacist fetishization or is this the end result of the Carlisle school assimilation process, where the Puerto Rican can exist completely as white, yet maintains the cultural authority to judge the Indian, using the Eurocentric lens of what makes an Indian? Rather than a syncretistic approach, the fully assimilated scholar commodifies the people he shares an identity with, packaged appropriately for white consumption.

Unchallenged as a Puerto Rican expert—made most efficient through the name alteration—Paul has been allowed to use every day people as the subjects upon which he gets to play out colonial fantasies that exotify our neighbors as much as they justify academia’s need for a person like Paul. Galleries show and sell his portraits and push his books. We must distinguish colleague from colonizer. In this modern rendition of the Red Man and Helper, Paul the Helper is allowed to serve his audience racist fantasy as academic rigor. His students, no doubt, are being told to study his work and his peers are taking this work into consideration when they think of today’s Puerto Rico Problem(s).

When Paul went up for tenure, he asked me to write a reference on his behalf, a perplexing misjudgment on his part. I detailed these critiques and concerns to the department chair, a white woman who’d done her best to bury the multiple abuse claims brought forward27, and Paul was awarded tenure protection. He continues to exhibit, publish, and profit from his studies of ‘real taínos’.

I’m left with a question to which I don’t really want an answer. Did Paul fancy me an Indian when I was in his university class, when he asked me to write as a reliable narrator of his academic integrity, while I spoke English and performed “civility”? If we had met for the first time today, after years of being houseless, living in a bamboo/tarp shelter we built ourselves, with my hair braided down my back, would his judgement be different?

Querido Boricua:

He does not get to judge you. We need to excavate our own histories, because we will never fit in America’s boxes. But America was forced upon us, despite our struggle, and that informs who we are. We know we are Boricua, a perfect mixture of Taino, Spanish, and African, as the myth goes. And we know what the Spanish did to the two other groups. But we are rarely told we were Indian, as the U.S. saw us, and what those ramifications have been under U.S. policies.

The assimilation process has yet to materialize because we’ve always been problem pupils, yet the attempt has been so complete that the lines between education and annihilation are blurred and our history becomes confined to what makes up European fantasy. The Puerto Rican students said they were not Indians, the Carlisle leadership as well as the federal government asserted that we were not Indian, yet Indian was the box that was available. We were Indian because that was the extent of their imagination. And they were sent to Carlisle on “USA grants”.

Over this last century, we’ve made huge leaps in taking over our school system, but for the last decades it’s been systematically dismantled. Today, our school system, the 6th largest in the U.S., continues to be slashed by the austerity cuts (this summer the University of Puerto Rico system lost another $100 million, 20% of last year’s budget28) and closures (nearly half the schools have closed in the last few years) and the remaining schools are riddled with infrastructure issues, blackouts, mold, asbestos, face frequent closure and have teachers taking on second or third jobs to make ends meet. Beyond finances, the unelected oversight board is closely monitoring how teachers and students spend their time, requiring increased automation when electricity is rarely certain, and holding teacher pay until they fully complied to use the new systems. Teachers are fighting just to get a single guidance counselor for their school.29 Not only are our students scoring among the lowest on math and English, but we are also backsliding on literacy and grammar in Spanish.3031

The trauma reverberates through us. It continues to scrape our names and our tongue clean of our family language. We have the most information about the Carlisle School because it was run by an American military officer in old military barracks, funded by the federal government. We also know some about Hampton Institute, now Hampton University, which was based on a school used by the founder’s parents for assimilating native Hawaiians. Puerto Ricans were also sent there. But I cannot overstate how much we don’t know, how much was lost because the victims had no recourse and trauma kept them from speaking up. The horrors we’ve learned about Carlisle and from Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is just the tip of the iceberg. America’s church and private-run schools, missions, and orphanages will require a similar Truth Commission to uncover all that happened to our youth, now our elders and ancestors, such as the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act (S. 1723/H.R. 7227), already being reviewed by Congress.32 Tragically, Puerto Ricans are completely omitted from the report issued by the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs33 which includes Native Alaskan and Hawaiians, and that is our work to do to make sure we are included in the implications of the final bill. Our Indian school era is a bridge that connects us with every Indigenous nation because just as they were made Indian in the eyes of settlers, so were we, and their struggle is our struggle. There is plenty of room for solidarity.

After all, Ruth was right about one thing: The people of Puerto Rico cling to the idea of absolute self-governance and resent America assuming the scepter of power in any wise. We fancy ourselves entirely capable of managing our own affairs in matters educational no less than political and we would have all American influence, in our schools as elsewhere, withdrawn.

We are descendants of the children sent to Indian schools, and we are problem pupils.

Bell, Genevieve. Telling Stories of School: Remembering the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 1879-1918. Stanford University Press. 1998. Page 6-7.

In the generation after the Civil War, America saw economic windfalls coming in that would go towards developing comfortable lives for white Americans and new European immigrants, but in order to process the new profits, i.e. turn newly stolen raw materials and land into ready-to-buy goods and services, they needed to fill masses of factory, servant, and farm jobs with Black, Indian, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Filipino workers, by sending them to assimilating industrial schools like Carlisle and Hampton Institute, now Hampton University.

‘The “Outing Programs” Human Trafficking at California’s Native American Boarding Schools: Supportive Testimony H.R. 5444 / S. 2907 the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the US’ by Jean Pfaelzer, University of Delaware. https://docs.house.gov/meetings/II/II24/20220512/114732/HHRG-117-II24-20220512-SD054.pdf?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR0Rk4M_Oha8vdrx8seDjhPKAEDkJN1t4sIXtVHBvjqQz3uc3CFsKdO3aRE_aem_QNCcqOg4MiwccxyrqjJlfQ

Semuels, Alana. “Segregation Had to Be Invented.” The Atlantic. Feb 17. 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/02/segregation-invented/517158/

Juan Santana student file from Carlisle. https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/student_files/juan-santana-student-file

At the time of US invasion, the Puerto Rican peso was valued similarly to the US dollar, but a in a single act in the earliest days of the takeover, the peso was determined to be worth just 60% of the dollar, immediately extracting 40% of the nation’s wealthy.

The Red Man and Helper. Vol XVII, No. 10. Friday, Sept 13, 1901. https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/sites/default/files/docs-publications/RedMan-Helper_v02n06_0.pdf

Navarro-Rivera, Pablo. “Acculturation Under Duress: The Puerto Rican Experience at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School 1898-1918.”

Atleast 59 students are known to have attended Carlisle at the expense of $250 per scholarship, totaling $14,750. Calculated for inflation to be equivalent to $528,487.47 in 2024. Note that it has been speculated that upwards of 100 Puerto Rican students actually attended Carlisle, though in some case they did not receive scholarships and so did not get counted in the tally of federal funds.

In the December 2, 1898 issue of The Red Man and Helper, Pratt writes: “General Eaton is one of Carlisle's staunchest friends, and we are glad that he has been selected for such an honored position as Commissioner of Education in Porto Rico, which he so eminently fortified by experience and influence to fill.” Carlisle was both and Indian school and a military school, so it benefited the new military government to send Puerto Rican kids to Carlisle so they could later be returned as trained officers.

Shaffner, Ruth. “Civilizing the American Indian.” Chautauqua Magazine. 1896. https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/sites/default/files/docs-publications/Chautauquan_v23n03.pdf

From a letter about attending a commencement ceremony at Carlisle published in The Southern Workman, Hampton Institute.

Etnier, Ruth Shaffner. “The Education Problem in Porto Rico.” The Southern Workman. v.30. Hampton Institute. 1901. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044018881094&seq=273&q1=Etnier

Osuna, John Joseph. “Education in Porto Rico”. 1923. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015008573365&seq=127

Alex’s letter, written in 2019. This letter was apart of a larger campaign of letters detailing Paul’s abusive behaviors and policies while at VCU. The campaign was presented to school leadership ahead of Paul going up for tenure, but it was purposefully ignored and excluded from the review process of his tenure application. Read the letter in its entirety here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1jV4HvEpgOm0yVGz1JRh64U_pSodWu2fA/view?usp=drivesdk

“A Real Taino” published by Paul Thulin on Feb. 20, 2024 on Instagram, in reference to his Indian hunting photo project:

A Real Taino -|I met him on top of a mountain|on a road becoming a path|And then a slide|I was told he was a real Taino|none of that bullshit| wannabe dress up types,|seeking USA grants|drumbeats, and sex in leather|I was scared|off grid and alone|good medicine for the pilgrimage|I did not know I was on|his hut was homemade|on top of the world|sporting a windmill and a solar panel,| a weathered punching bag swayed in the breeze|-|a huge mastiff mutt the size of a horse was chained to a post|- barking, teeth flaring, attack leaps -|"Baracutey, some Gringo looking bastard is on our earth. You want me to eat him?"|-|a skinny, sinewy, taut man with glowing skin appeared|All clay, sunshine, and herbs|Wrapped in a Hendrix T shirt and worn jeans|Wrapped in a Hendrix T shirt and worn jeans|"No, not yet but maybe in a bit."|-|I felt my fraud|panic inside me wanting to run|Who the fuck am I to stand|in front of a real Taino?|-|He smiled the biggest smile I have ever seen|One corner of his lip stretching to the other|A valley of humility and peace|surpassing grand|A snarling growl and snout in air|" His smell is not bad? Baracutey. I think he might be ok| to sit with. He might have treats."| Raising a back leg he pissed on a post|BAM!|Baracutey punched the boxing bag|the impact thundered and folded the cowskin|"I am so hungry. There is a restaurant down the|mountain. Will you buy me lunch? I am so hungry."|Lunch?, I thought.|Go back down that damn mountain.|Did I make a mistake?|Is this the path to indigenous knowledge?|I nodded.|He walked back into the house|the mastiff huffed|and collapsed on the ground|Dust kicked up in the heat|And when it settled|The dog was already snoring|I stood dumbfounded|I had been transported|To another realm|A part of me had run away indeed|But that part needed to go|-|I took three steps|And passed through two doors|One of a hut on a mountain in Utuado|the other into the mystical universe of a hungry Taino|A Real Taino|

See Alex’s letter, footnote 25.

Paul…. The Helper 😩😂